A new image. A little play today instead of a philosophical harangue. A philosophical display?

A new image. A little play today instead of a philosophical harangue. A philosophical display?

I have rarely watched party conventions. They are filled with hyperbole, grandstanding, speech-making excess. All the emotion-laden hucksterism we usually joke about at other times. I distrust decision-making based on limbic response to blatant attempts to “inspire” me. Inspiration, to my mind, should be an emergent property of action, of character in service to sound ideas, to a self-evident moral response to circumstance. I am inspired by what someone does, is doing, not by the particular rhetoric of promises and assertions that I should believe in something as embodied by the speaker when I have not seen that speaker doing any embodying.

In this, I suspect I am in a minority. People seem largely to prefer cheering to deliberation.

In any event, I have usually made up my mind well before the convention, so unless a dark horse comes riding onto the floor, there are no compelling reasons for me to subject myself to what amounts to four days of self-congratulatory back-slapping, bragging, and crowd-rallying, the last of which I deeply mistrust. Too often, large crowds end up displaying the least dependable aspects of human nature. The momentum of large groups can overwhelm reason and restraint and end in riot. And by riot I do not necessarily mean the physical kind. There are many types and they are all destructive.

But conventions are instructive at a distance. You can tell a lot about the people in attendance, supporting them. This year the difference could not be more stark, and on a very simple metric.

The crowd component I mention above…

The Democratic convention this year was held online, virtually, in order to handle the pandemic in as responsible a way as possible.

The Republican convention was held in the traditional way, bringing crowds together, regardless of the pandemic and its potential consequences.

That’s pretty much all one needs to know about the difference between the two parties right now. Because the one is banking on its ideas and its embrace of common sense and a modicum of concern. The other is banking on the momentum of the mob, and for that to be a factor, people have to be in the hall, in sufficient numbers for the excitement of the party to overwhelm reason.

Much has been said about the nature of our democracy. This has always been a topic, but it has grown into a major factor. Are we a democracy? If so, why do the parties make it hard for some people to vote? Shouldn’t the right to vote be axiomatic and unquestioned? “The Founding Fathers____!”

Fill in the blank. It’s said they distrusted democracy, hence we have a republic, which is held up as some kind of anodine to democracy. it is said they loved democracy, hence humbled themselves before the dictates of The People. You can find quotes to support both positions. Like pulling quotes from the Bible, one can defend almost any assertion based on what the Founders said.

Some of which was unequivocal. Much of it was implied. A good deal was personal opinion.

But it seems evident that they recognized a basic truth about human nature.

People do not live wholly by ideas.

People live where they are and by what they feel and in relationship to who and what they know. One way to put it is that people are less deliberative and more reactive.

For instance, you’re a colonial listening the the reading of the Declaration of Independence and you hear those words “All men are created equal.” How do you feel? Quite likely, if you are a patriot of the day, you hear that and think of King George and think “He’s no better than me, we are in fact created equal!” And that feels good, feels right.

What you do not do is turn around and say, “By god, that’s true, we should free our slaves and stop killing natives! We’re created equal!”

The idea has a limited range of effect. It may work in one direction, but not the other. Certainly, looking at history, this is a perfectly accurate reading. Ideas do not change prejudice, behavior, habit, or desire, not unless those ideas already in some aspect conform to one’s prejudices, habits, and desires. It is inarguable, based on the evidence of things done, that people ratified the Constitution and the Bill of Rights and then continued living as though none of it actually applied to them. In each period of our history, a struggle has occurred over what our principles say and what we wish to do. All men are created equal, except some, whose situation we do not wish to change because it will cost us, and besides, those words only applied to me. Freedom of speech, of course, except for that newspaper publishing things with which I disagree, so I will burn it down. The franchise should come with equality, which is expressed in our Declaration, except for people I know who will vote against what I want to do, so no.

This is not a ridiculous idea. This is privilege, short-sightedness, and the consequence of people fearful of sharing something they only just now won, and not trusting that it means the same thing to others as it does to them.

And besides, life is competition, the struggle for advantage, cut-throat and dog-eat-dog, and abiding by lofty principles will erode gains made by one group in favor of other groups with no obvious affinity.

The Founders knew people were like this. It is why they created a system that worked against any one person or faction gaining and keeping power and also why they distrusted pure democracy. They took a very long view of how this might evolve, and some if not all of them knew it could get ugly.

But what choice did they have? They came very close to re-instituting a monarchical system they had just fought a war to be rid of. How to prevent that obvious desire? They heard from people who were happy and proud to be free who then wanted to turn right around and put themselves back in the same chains. No doubt they thought it would be different because they would be “our” chains. Then, too, they knew they could not simply overthrow the entire system already in place without releasing the jackals of civil war. We nearly had that anyway over the first decade or two. I think they knew it was inevitable as well, but had no idea how long it would take, and established a set of promises that gave legal pretext for suppression when it came.

The history of the Republic is underpinned by large segments of the populace acting on the assumption that certain rules did not apply to them. That to “do the right thing” according to those ideas would have meant not doing what they thought they had been given permission to do in the first place. Colonizing, settling, exploiting, intruding, and embracing intolerance when necessary in order to keep doing what they believed to be their right to do. What became the moneyed class, capitalists, assuming they could ignore the principles as long as business improved. And later, certain Citizens who assumed the law did not apply to them, because they were important and those pressing complaints against them were not.

Because ideas rarely trump that innate limbic response which can from time to time inform crowds and overwhelm reason.

When the charge “the Founders never intended” is leveled during times of disputatious turmoil, we should stop right there.

Yes, they did intend. Because they knew the ideas they sought to elevate as the foundation of a principled polity would take time, conflict, blood, and riot to instantiate. Yes, they did intend that we go to the mat over these things, because they knew it was the only way behavior changes across populations and even within families. They knew because they had just been through a class in exactly that. The arguments they made to Britain and the Crown over representation, taxation, treaties, self-government—arguments that were perfectly reasonable, even legally sound according to British law—had failed to move the king and Parliament, because that “august” body and George III simply did not feel their laws applied to Others. The entire war could have been avoided if ideas had immediate power as self-interest and pride and passion. The Founders had watched England squander the good will and potential of the North American colonies over questions of privilege and the assertion of authority. In other words, they had watched human stupidity wreck a sound relationship.

So they knew what could and would happen when ideas—especially new ideas, ideas based in abstracts (albeit with profound real-world consequences) ran afoul of people being who and what they were.

And, yes, what they created took that into account. So what they “intended” was that we hash it out. They knew we going to fight about these things. All they did was set the ground rules and sprinkled some idea throughout to give us the right things to fight about. Did they cover every contingency? Of course not. How could they anticipate what might change? Oh, wait—they did. The Ninth Amendment.

The flaw, if flaw it is, in the system is that with growing success materially our interest in participating intellectually tends to wax and wane. That’s why Jefferson stressed education. But even that is no guarantee that we might not come to a point where most of us could be willing to throw the whole thing out for the simple expedient of having Someone Else make all these difficult decisions. As well, the more complex the world becomes, the likelihood that enough of us might have the time, intellect, or interest in understanding these complexities well enough to make the kinds of judgments we elect representatives to do grows smaller. It’s not impossible, but look at where we are now.

But the fight goes on and out of the kicked-up dust and spit and broken teeth some kind of emergent property forms to take us to the next step. It almost never looks like we’ll make it, but at each one of these periods something comes about that carries us through.

Because ultimately we move against demagogues. Not because we disagree with their positions or dispute their ideas, but because we will not be dictated to. Persuaded, seduced, enlisted, certainly, all that, and at times we find ourselves with leadership taking us questionable directions because the program was presented with flowers and candy, but when the specter of bullying autocracy becomes evident, we bristle.

It’s not a method I am comfortable relying upon.

But to the point, we have an ongoing tension between who we want to be and who we are. Slowly, oh so slowly, over time, we have changed, becoming closer to an ideal which, itself, has changed. You could ask almost anyone if they agreed with that initial statement, All Men Are Created Equal, and for the most part find agreement. Of course, that’s what it means to be an American.

Then the other shoe falls. All men. And, in fact, all people, are created equal. All.

And then, if you press it, you find equivocation. When it becomes clear that you mean they should treat everyone equally.

Well, wait just a minute…

No, people don’t like that. For many reasons, not all of them as capricious as it might seem. For the most part, the discomfort is mild and usually unexpressed. But it’s there, and given the proper nourishment, erupts. But over time, we know the principle is better than the impulsive rejection.

Gradually we become who we wish to be. Sometimes it takes generations. And sometimes, there has to be a very public, very bitter contest over it. And if we’re lucky the reasons for embracing the ideas over the impulses show themselves starkly. Then we have a choice. Who do we want to be?

Two conventions. Just the difference in the way they were handled is indicative of the choice.

As to the content…well, that’s been clear for a while now.

This is not, should anyone believe otherwise, a plug for one party or the other. Parties evolve, morph, turn into their opposites, encompass positions that are often far from ideal. No, I’m not shilling for one party or the other. I’m talking about where the human beings are right now. Where you find the clearest expression of human sentiment, ethics, and, yes, morality. I’m talking about people trying to be one thing or the other, but really I’m talking about people trying to be the best version of what our ideas have shown we can be. Where do they happen to align now? Where will we find the better angels of our nature? The room is not so important, although just now the nature of the room itself is telling, but who is in it.

This is a mini-rant.

I have no idea how much this influences the times we are living through now, but—allow me to set the stage first—part of my job (day-job) is reading books for possible inclusion in inventory. These are generally self-published. In spite of everything, I have become…an editor.

As a youth, I experienced impatience with what have become known as Grammar Nazis. As with so many elements of good writing, I didn’t care that much as long as meaning was conveyed and the story moved along. Event was my drug of choice, character not so much. The elegance of the prose…well, sure, but it wasn’t necessary.

So I thought.

Years later, having labored at my own fiction, I found myself pitying that young idiot. Event means nothing unless character conveys impact. The elegance of the prose is primarily a property of the kind of writing that allows a reader the full range of experience through a story. Style, substance, character, plot. Take any one away, the text falters. Make them work together and you get something worth reading, perhaps even memorable.

And now I see the downside of haste and the ease of Getting The Book Into Print regardless of its quality. Or qualities.

And then I listen to the speech of our public figures and can’t help but wonder if we are in a state of communicative disarray because they (not all, but some, perhaps many) never learned how to write or speak well.

Once upon a time, Rhetoric was taught as one of the primary Arts.

There are many reasons we should revisit that.� I will say here that Grammar (as it was taught to me in school and probably as it is still taught) is no substitute for a full course on the Reason To Learn To Write Well.

If we cannot speak to each other intelligibly, how can we ever hope to solve problems?

Regarding the books I read for my job, most of them, usually, are written in what I would say is serviceable prose. Nouns, verbs, adjectives, subjects, objects, all those elements are mainly in their proper places and meaning comes across.

But sometimes, where it matters most, a significant handful of hopefuls write in what I can only assume is a manner (mannered), a style they think is “literary.” Convoluted constructions, run-on sentences, what Mark Twain called “second cousin words” instead of the right ones. And attempts at conveying…something…of which the writer has no real understanding and covering that lack by piling on Important Sounding Verbiage.

Primarily, the problem is the writer does not actually have a grasp of what they are trying to convey. Secondarily—and fatally—they haven’t taken the time to find out how to do the craft.

Likewise with so many second-rate pundits and politicians.

We live at a time of unprecedented access to public dissemination. In the past, you couldn’t get your words published unless they could get past an editor. Now we can put out any damn set of sentences we want with no one to tell us we shouldn’t.� Self-publishing has created a glut of bad prose and an entitled generation of self-important blatherers who think their words are worth the same time and attention as someone who has worked hard to learn the craft and—most importantly—understood what is important to say.

And I’m not talking about paper books or even ebooks. Multiple platforms exist to allow access to people for anything they feel moved to say. In the sense of it being a forum, all the social media outlets are functionally publishers and too many people think they’re worth reading by putting something on them.

The result of which is a degradation of public discourse. Hitting Enter has become the sinecure of too many empty minds, vacuous ideas, and poorly reasoned diatribes.

Something about seeing bad prose on a page between the covers of a physical book makes it more obvious.

Years ago I became aware of a subset of wannabe writers who felt they could be writers while eschewing reading. This baffled me no end. To begin with, why would you conceive of the desire to be a writer if you did not already love reading. Of course, the truth is, they do not want to be writers. They have no idea what that would be.� What they want is to be Important. Noticed. They want a stage. They assume the desire is sufficient to the purpose.

Likewise for people who wish to be Thinkers without troubling themselves to learn how to think. But of course, they don’t really want to be Thinkers. They want to tell others what to think. They want to be Important. Noticed.

We have given them a stage. Many stages. And since the price of admission to the show is usually free, well, as they used to say (and may still) you get what you pay for.

Please. Communication is not a trait like hair color, height, or eye color. It has to be learned. You have to work at it.� And just because you learned how to talk does not mean you automatically know how to speak.

Thank you for your time and attention. I’m going to go read some more books now.

I took a walk this morning, around my neighborhood. You should understand, in some ways I am a very typical urban dweller. I don’t know my neighbors. We don’t hang out together, we don’t have each others’ phone numbers, we aren’t pals. Nothing deliberate, just a product of the car and the phone and the pace of our lives. When we moved into this neighborhood a quarter-plus-century ago, we would take evening walks and see many older residents sitting on their porches. Some would wave and smile. I finally realized that some of them, at least, were indulging a practice from a faded era.

They sat on their porches in the evening specifically to greet passersby and maybe have conversations. As these people disappeared—moved, died—we stopped seeing this. In the last few years we have had an influx of immigrants—Hispanics, Eastern European, Asian—and again we see this practice.

I don’t know how to engage this way. I am, in fact, a basically shy and self-conscious person, and I can’t imagine most times anyone wanting to talk to me who doesn’t already know me. Maybe that’s a symptom of the urban social matrix, too, I don’t know.

But lately there have been even fewer. The streets are emptier.

Not abandoned. Lawns are tended, sidewalks swept, plants on steps or railings watered. The evidence of human presence is as visible as ever.

The silence is different. Even though I have rarely indulged speaking to strangers just because they were waiting to be spoken to doesn’t mean I never appreciated their reality. We would walk by and wave, give a good morning or good evening, smile. It doesn’t take much to reaffirm our connection as human beings.

I doubt I will change my basic nature when this current situation is ended. I’m just not like that. And I do value the structure of contacts from before. Choosing your friends has, I think, more significance than having people thrust upon you because there are no other avenues for interaction.

But I will appreciate them more, I think. The sounds, the scents, the frisson of neighbors in the now.

I wish them well.

Trying to make sense of the argument raging back and forth in this country over civic duty, social courtesy, politics, and the evident incommensurability of conflicting “lived experience” among the various parties reminded me of something the other day. I laughed and shrugged it off and thought well, yeah, that’s apt but silly.

Then I thought, if we filter out the presumed topics and just look at the behavior, maybe it’s not so silly, Because, really, it is silly.

When I was in first or second grade (yes, that far back, that deep down), I was beginning to learn how much I didn’t fit. I didn’t know that was the issue then, just that I kept looking at my “friends” and the teachers and the whole thing like some foreign country where I didn’t speak the language. Spring came around, and we were going to do a Maypole Dance.

Why? Beats me. I mean, seriously, a Maypole Dance? For grade schoolers? Obviously, we didn’t know what it meant. As for the teachers, it was just this neat thing they could use to teach…well, I assume cooperation, group unity, and make us feel pleased with an accomplishment. I have no idea.

But I was excited as everybody else.

We learned the steps, practiced, got good at it. It would take place in the gymnasium and it was an early evening event. Parents and interested parties would be present. A Big Deal.

I remember being informed that the boys would wear green bow ties and the girls would wear pink ribbons. (The streamers around the pole matched.) Well, I owned a green bow tie, so that was fine. I showed up prepared.

Only to find out that my bow tie wasn’t good enough. Wasn’t allowed. No, we were to be fitted with these great big paper things, way oversized, and, frankly, to my eye, stupid things made of green tissue paper. I took one look and thought Nope, ain’t gonna happen, I’m not wearing one of those.

Whereupon I proceeded to Make A Scene. I made things difficult for the teachers. I even hid under a desk rather than be subjected to the indignity of being forced to wear one of those silly, stupid, childish Things, especially when I already had a perfectly good, normal bow tie. The argument that I would look like everyone else did not impress me. Why would I want to do that? The argument that this was a group thing and we had to conform for it to look right bounced right off.

In the end, I was made to yield. I endured being fitted with one of those idiotic (I thought) kiddy ties.

Then the Dance happened and I forgot all about it.

The people stamping their feet and getting all huffed over wearing face masks remind me of that intractable seven-year-old. “I ain’t gonna do it! It’s silly! I don’t wanna!”

I am extending it, though, to a whole range of social issues, and watching the reactions of those who refuse. Try as I might, I cannot find it in myself to sympathize, not with the screaming, red-faced, intransigent self-centered, entitled drama addicts who think because of this or that or the other requirement they are somehow being so unduly imposed upon that civilization is about to fall.

I am willing to discuss the issues in reasonable tones, with facts at hand, and logic and rational consideration on tap. But the comparisons are absurd. No, your constitutional rights are not disappearing because of a public health measure. The Constitution does not afford you the “right” to live any damn way you please if others are put at risk.

But those who are stoking this fire with fuel know that very well. They know their audience. They know they’re dealing with people who can’t tell the difference between inconvenience and moral necessity.

I Want and I Don’t Want are the only two positions that get any traction, it seems.

I recall my unreasoning and unreasonable seven-year-old self because that seems to me the exact parallel. Things have gone a certain way for so long that this would seem a perfectly reasonable reaction.

The good news, though, is this: I was the only one in my class chafing at the requirement to wear the same green bow tie as everyone else. In the same way, the red-faced, distraught, petulant dissenters over face masks, I believe, are also a small minority. They only seem like more than their numbers because they’re making a scene, hiding under their desks, and everyone else is staring at them.

Amplified tantrums.

We seem incapable of looking away, of ignoring the traffic accident, the class clown, the guy with the End Of The World sign screaming at the pigeons in the park. The attention feeds the fit and he seems like a multitude.

In the meantime, the rest of us are respectfully doing what needs to be done to have a successful dance.

Sit down and put your bow tie on. It’s not the end of the world.

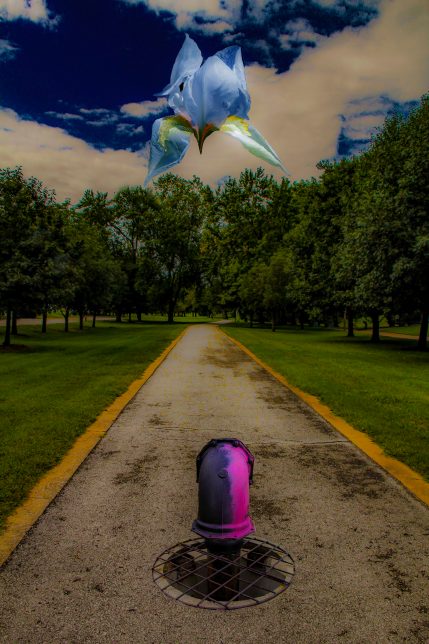

Just playing around here. I shot this image on the road back from Houston last November, intending to play with it. I finally got around to it. Here are three versions. The first is pretty straightforward, slightly “corrected” for contrast and color, but pretty much As Found. The next two are variations I worked on it for effect.

Enjoy.

I have always been a little perplexed by statues commemorating some historical figure. Public memorials to long dead people who may or may not have done what the memorials claim for them seem dubious at the outset. A form of idolatry, though not in a religious sense (not for me). The commemoration has less, it seems to me, to do with who these people were than what they represent for the people putting up the statues.

Abstract statues are different. The soldiers in certain war memorials, who, while perhaps based on living people, are not of said people. They embody All Who Were Concerned and go to the events memorialized.

Of course, certain statues of specific people over time become abstractions in much the same way. Enough time passes, few know who that person was, its place in public life changes and its meaning shifts. It stops being about the person, even about the history, and becomes decoration. At best a distillation of some collection of civic sentiments having virtually nothing to do with what it was intended to represent.

Along comes a sudden awakening of that same public consciousness and revelations emerge as to who and what that statue was all about when it was erected and now we are divided over what to do. Just as these monuments were almost never about the people depicted but about the sentiment of those creating the memorial, so too are our deliberations about what to do with them now that the underlying history has become very publicly visible. It’s less about the memorial than about current sentiment.

Now before anyone thinks I may be about to dismiss that current sentiment, let me put it to the forum: if the contemporary sentiment was valid enough at the time to serve as justification for erecting a memorial, why should present sentiment be in any way less valid as justification for removing them?

We’ve changed. Our values are expressed differently. It is completely understandable that what was held up as representative of who we were once should no longer represent what we are now. Statues to Confederate “heroes” should rightly be reassessed and dealt with accordingly, especially as the history of the memorials shows us that when and under what circumstances said memorials were erected had virtually nothing to do with the persons depicted. The vast majority were reimaginings, revisionist representations of glamorized if not outright false characterizations of actual history. In a very real sense, many of them are simply lies.

As are most such things, if we dig deeply enough.

Sometimes it’s just a matter of sanding off rough edges. Sometimes it’s a complete rehabilitation

But there are also those which have aged out of any relevance other than the æsthetic impact of the work itself. (The outrage the world felt at the Taliban destroying the Buddhas in Afghanistan was driven not because of who or what Buddha may have been but because those statues had become a cultural touchstone as works of art.)

The question is, how long is long enough to distance a piece of art from the shortcomings of its source material.

When, in other words, does a monument lose its original intent and become a part of culture apart from that origin?

Take the latest debate in my hometown over a statue of Louis IX. St. Louis. It stands before the main entrance of the St.Louis Art Museum, a noble figure atop a horse, right arm raised bearing a sword. (The sword was stolen at one point and recovered after a much publicized hunt. I may be misremembering, but when it was put back, it was done so upside down, which made the sword over into a cross, but that could just be my faulty memory.) There is now a debate about removing it because—

Well, because Louis IX was an anti-Semite and led two Crusades and burned books. (He is the only French monarch to ever be canonized, which suggests that all these traits were at the time seen as positives.) He died in 1270. Because of his sainthood, place-naming in his “honor” became popular.

The town of St. Louis was founded in 1763, almost half-a-millennium after his death.

I doubt many of those first colonists knew the details of his actual life. Even less do I think my contemporaries know much about him or have even given him a second thought. The statue is cool in a kind of Victorian bronze-revivalist way. At the time of my hometown’s founding, Louis XV was on the throne, soon to be dead and succeeded by his son who would be beheaded by the revolutionaries in Paris. If anything, the naming was as much in his honor as the reigning French monarch with a nod to the Catholic Church through the only sainted king. In other words, purely political.

In what way is the life and opinions of a 750 year dead French king relevant to the current spate of monument removals?

Obviously, his life and deeds are in many ways odious to contemporary sensibilities. But the fact is, he was completely one with his time and place. He exemplified mainstream European thought. Catholic Europe was almost entirely anti-Semitic and the Crusades were popular as ideas (if not as actual enterprises, since by Louis IX’s time they were beginning to show signs of stress). He expanded the Inquisition in France and he burned the Talmud. Few if any of those for whom he was a leader gainsayed any of this.

The same cannot be said of the Confederate leaders. The debate among those who clearly identified as mainstream was heated, public, and led to actions not supported unilaterally at the time, and constituted a repudiation of certain ideas and actions which were under question and which would soon lose to a groundswell of moral reaction. Monuments to the leaders of the rebellion are political statements in ways the statue of Louis IX simply isn’t, nor was when erected. In short, the statue of Louis IX is an abstraction as opposed to a statue to Robert E. Lee, which was not and is not today. Louis IX has become a malleable nonspecific symbol representing another abstraction, namely the place-name of a city which is itself become dissociated from its origins by virtue of changing hands thrice.

In case there is any doubt of my motives, I intend only to shed a light on causes and impulses. We’re caught up right now in a spate of trying to redress grievances. A perfectly legitimate movement and in many cases long overdue. Personally, I never did understand the whole Christopher Columbus thing. He bumped into the Western Hemisphere expecting to land somewhere else and then set about acting the power-mad little tyrant until his titles were stripped. A good navigator who still got he actual size of the planet wrong and managed to not only unleash misery and desolation on the natives he found but got a lot of his own people killed as well. All in all, a serious screw-up. The continents weren’t named after him but after a mapmaker, so I always wondered, after learning a bit about him, why the veneration? His only significant legacy was the establishment and justification of trans-Atlantic chattel bondage and the introduction of syphilis to Europe. Why anyone put statues up to him in the first place (here) always baffled me. He hadn’t been the first one from over there to find this side of the world and he wouldn’t have been the last. In my opinion, his idolization was a species of self-congratulatory holiday creation, an excuse for a celebration (of what?) and a propaganda tool to flense the past of dubious aspects in the name of making a “purer” set of founding myths. Motives should be questioned at all levels.

Perhaps it ought to be considered that hagiography ought not be allowed in public memorials. Abstract sculptures, idealized forms, universal archetypes, fine. We can argue over ideas and representational elements. But to cast a statue in the form of an individual for things which may be of dubious moral provenance is probably a bad idea, with very rare exceptions. (What is done privately, on private land, is another matter.)

But there is also the question of actual relevance, both pro and con, when it comes to revising our national ethos. Making snap decisions resulting in vandalism and arbitrarily lumping certain styles and periods into a one-size-fits-all reaction may not be the smartest thing. (Ulysses S. Grant and Robert E. Lee represent very different legacies, but if you don’t know history—and, lord, so many people don’t know history—then it might appear that tearing them both down for a single reason is justified.

For myself, I have serious problems with the whole idea of veneration. This country is not a theocracy, erecting statues to our presumptive “saints” is not a tradition I care to support. Famous for being famous does not merit a public monument on public grounds, especially given that what may actually be the reason for praise does not equal the sum or even much of a part of the individual. (As I say, what is done privately, on private grounds, is different.)

And it is all propaganda. Consider: the Russians understand this very well, which is why after the collapse of the U.S.S.R. all the public monuments to “great” Soviet leaders were removed and stored in “graveyards.” They knew that in order to move on, they had to rid themselves of the visible instantiations of a past no longer valid for them. They couldn’t do that with all those dead ideologues watching them from every public building, park, and square. Such things matter.

There will, however, be those instances where the object in question no longer has that function. It has become a work of art, apart from, severed, from what it may once have represented, and now is just a thing of beauty (depending on one’s taste).

We have the relative luxury of knowing the history and provenance of all those Confederate statues. We don’t have to guess at why they were made and placed where they are. Remove them, by all means. They are propaganda of the most base sort.

Remove Louis IX as well, if must be. But Europe didn’t even know this side of the world was here when he was a monarch and his policies, while in many ways repugnant, are not the stuff of current controversy. His statue symbolizes nothing (to me) beyond a naming protocol for a new town and his legacy…well, I suppose one could make an argument that he was one of a thousand years of ecclesiastical abuse and moral dubeity, but I can think of many closer to our time far more worthy of repudiation, none of whom (probably) took any inspiration from a 13th Century Crusader who died of dysentery.

He was a patron of the arts, though, and credited with revitalizing architecture in France and contributing to the Gothic school. Which is one reason his statue is in front of an art museum.

And it is a cool statue.

The question came up recently among friends about answering the claim that, concerning the wearing of a mask these days, “I have freedom of choice. If I choose to risk getting sick, it’s still my choice.”

My reaction was basic, which I will reveal at the end of this.

Choice is one of those perennial topics that rises and falls with public fashion. We link it to our ideas of liberty the way we link certain colors and seasonal clothing. At least until it really matters, but then we tend to dismiss it as a right and turn it into a species of moral determination that brooks no debate. We have it or we don’t. Period. Mitigating circumstances, point-of-view, necessity—and it is almost always the unaffected decrying the tragedy of permissiveness when someone whose situation is unknown, alien, or unfortunate seeks redress through choice which, all things being equal, most people never have. Or have to exercise.

Making a choice because the outcome is important means weighing options, reviewing evidence, considering multiple factors. It is a matter of consideration, not a reflex, or, worse, playing to a script because it sounds righteous. Denigrating people who have to make choices, who do that work, is done by people who probably have never been faced with a critical issue that requires thought, maybe sacrifice, and the knowledge that what choice is made affects others beside yourself.

I’m being categorical here because listening to and watching some of the protestations over the wearing of masks and seeing them “masked” as a matter of personal choice stirs my blood a bit. I’m sorry, but no, you are not making a choice based on reasoned consideration of viable options. You’re just saying you don’t want to be bothered. It’s too much trouble. It feels funny. It’s inconvenient.

Because all the nonsense about this being a violation of rights is empty posturing. You’re just a selfish jerk who probably doesn’t obey traffic laws very well, either.

And if you add to that the excuse that your current fearless leader has given you permission to be a jerk, then I will add that you’re a moral coward as well.

Because this is on you, as an individual (which is what you’re claiming, after all), defending your right to choose. Offloading the responsibility onto the blind mouthings of that empty suit—well, that’s more of the same, isn’t it?

You just can’t be bothered.

So, no, this isn’t an example of choice in action. This is an abandonment of all the factors that go into making choice a valuable right. If you were actually exercising that right, then you would go somewhere and isolate yourself from human contact until a vaccine is available. That would be the reasoned exercise of the right you’re claiming. Putting others at risk just because you don’t want to be bothered…well, that’s just lazy self-centered blather.

And, yes, since you ask, that’s really how I feel.

Stasis is impossible. Somewhere things always change. We can ignore it or inform it, but we can’t stop it. Right now, we’re in the deep throes of coming to terms with the effects of trying to not only stop change but reverse it. Time to get a grip.