Given the subject of the last post, I feel this is appropriate. Add a little light to the dark.

Tomorrow—June 23—is the 15th anniversary of the closing of Shaw Camera Shop. I was there on the last day (and at least one day afterward) and saw it shut down.

I grew up there.

As I’ve noted, I became interested in photography when I was fifteen. Dad gave me his vintage Canon rangefinder, bought me a small lab—Acura enlarger, a few trays, tongs, mixing bottles, a plastic film developing tank, a safelight—and I was off. Interestingly, I now recall, we bought all the darkroom stuff at, of all places, Famous-Barr. They had a complete photographic department then.

Soon after I began making my first messes, photographically-speaking, we started hanging out at Shaw Camera. It was close and had more goodies than the other close one, Jefferson Camera. Besides which, we almost immediately took a liking to Gene and Earline.

Physically, it filled the ground floor of a large two-story building near the intersection of Shaw and Vandeventer. The corner building contained a liquor store—Bus Stop Liquors. Catecorner across Vandeventer was Irv’s Good Food, which was immortalized in Glenn Savan’s novel, White Palace. It was the classic greasy spoon diner. The cook was an ageless fellow right out of a Woody Guthrie world named Earnie. On the other two corners were gas stations, one of which closed down (the one directly across the street from the Shop) before I started working there.

It was also right up the street from Missouri Botanical Gardens, which became a major customer.

The neighborhood was old and, as they say, “in transition”, so for years it was a mix of urban yuppie and down-and-out Section 8. Highway 44 was visible from the front window.

The store part was bright—a long counter that turned in an L about midway in, with glass cabinets behind a central rack on which were photofinishing order envelopes, the phone, various catalogues, right next to a counter containing the bins for finished work and the cash register. The back half contained two rows of shelf space on which one found supplies of all sorts. When I first walked in there, it was a cornucopia of cool stuff. If you wanted to start up in photography—the whole thing, shooting and printing—Shaw was the place to go.

Along the right-hand wall, midway, you came to an alcove. A door within opened to another large space which housed their collection of cameras and other assorted collectible equipment. (The collection was world class and included an all-mahogany 8 X 10 view camera from the 1880s. It drew the attention of serious collectors, including once Martin Barre of the band Jethro Tull, who wanted to buy it outright. Earl wouldn’t come down enough for him, though.) This room had three corked walls. One was taken up with a white background against which Gene shot passport pictures. The other two were used to hang pictures. Customers could display their work.

Proceeding down the center aisle, back in the main shop, you reached a wide access that could be barred by a heavy accordion steel gate. They’d been robbed once. Bad enough that the thieves stole camera from the shop, they had gone back into the lab and opened every single box of paper, exposing it all, putting the shop in serious trouble. The cameras were insured, the material wasn’t. The small area immediately through this access contained the lunch counter and the copy stand. To the right were two doors—one to the bathroom, the next to the office.

To the left was another wide access, which led to the lab space.

The building had once been a bakery, so this entire back area was done in polished white brick. (A great uncle of mine had actually worked in the bakery, in the 20s.) A separate room had been built square in the center of this huge space, and inside that room was the darkroom. Three enlargers, standing alongside tray set-ups. Everything was done by hand. No automated printing machines at all.

At one time this section had been leased out to a film sound-striping operation, wherein the sound recording part of movie film was added to raw film. This was a separate business from Shaw. Part of the chemistry these folks used was carbon tetrachloride. They spilled some one day—a whole bottle. They took their time cleaning it up and the fumes drifted into where Earl was working. At that time she wore contact lenses. The carbon tet vapors his the lenses and shattered them. Earl had no corneas after that and when we knew he she wore very thick glasses through which her eyes looked truly weird. That she could see at all was amazing, that she could see as well as she could defied reason. The film-striping company was asked to leave after that.

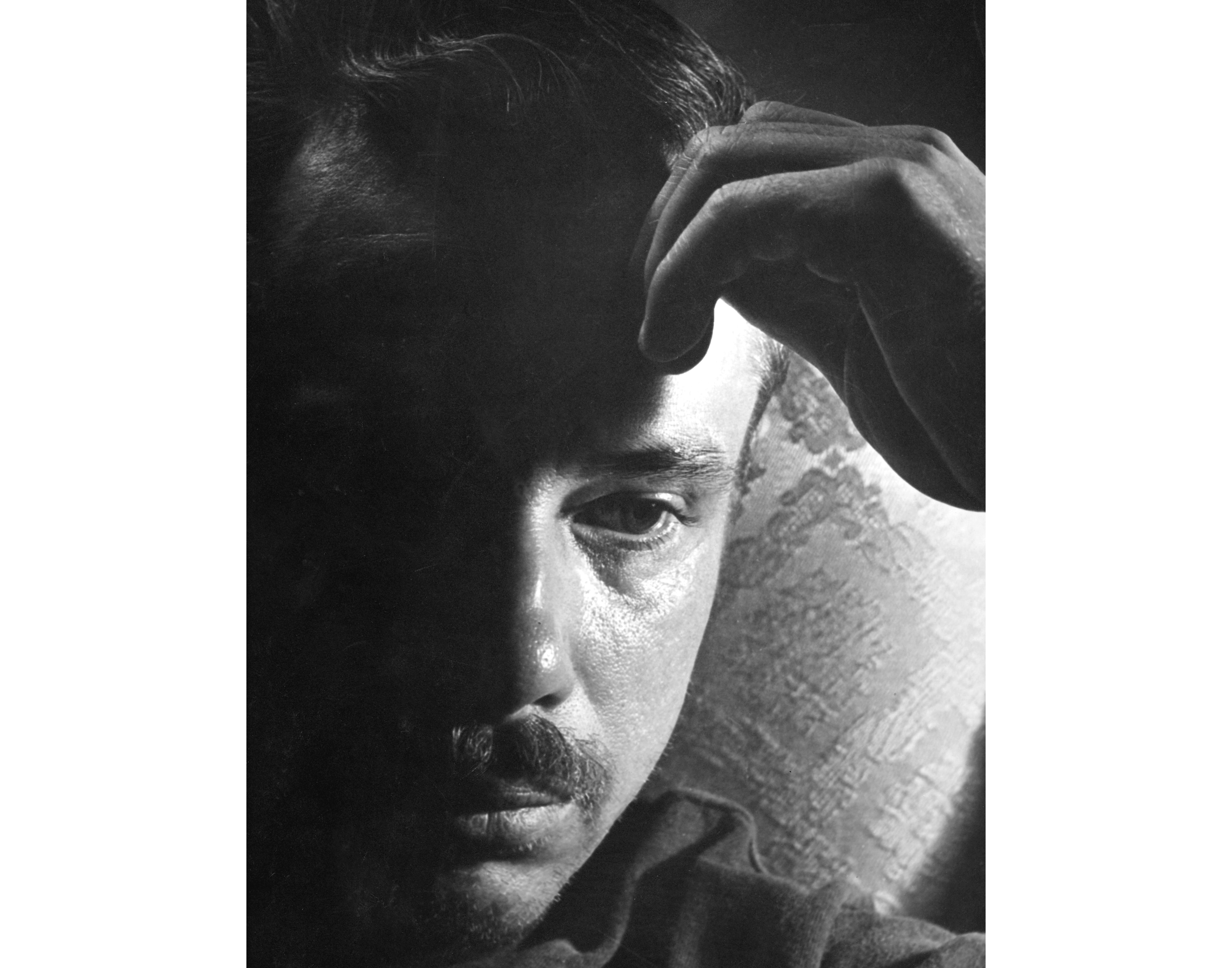

Just for reference, here is an old photograph from a newspaper article about the shop and Earline, from 1964.

This was before I knew her and before the accident.

I went to work for them in 1972 as part of the first Distributive Education program at my school. Actually, it was before that, in the summer. I’d hoped to keep the job all that year. But I was a terrible employee. At 17, I simply didn’t know what I was supposed to do. Not the lack of training, that was a given. But the idea of holding a job, of being a self-starter, of being responsible—I didn’t get it. So they fired me. I deserved it.

I had three more jobs between then and when they rehired me in January of 1976. By then I’d figured out how to be an employee and Earl took a second chance on me. Apparently it paid off, because I worked there until June of 1995.

Most of our work at the time was custom. Fine prints for particular people. We did only black & white. Color work we jobbed out and we had a couple of labs for that, most of which are gone now. For the amateur photofinishing there was Rainbo Color. Custom transparencies, Master Slide. They later added custom prints as well. Eventually, there was a lab that did cibachrome prints, Novacolor. And, of course, there was the Great Yellow Father—Kodak. But we did the black & white.

A couple years after I went back to work for them, we got into the yearbook business. For a few years we were printing all the work for the three largest yearbook photographers in St. Louis—Vincent Price, Hal Wagner, Lyle Ramsey (I think, memory may be playing tricks with me)—and had to add new equipment and hire new people. Earl was still lab manager, but more and more the daily management was left to me, while Gene handled all the retail.

As I mentioned before, they adopted me. When they realized how serious I was becoming about writing, Earline gave me an IBM Selectric for a Christmas present. (Later she gave us our first computer, a first-generation MacIntosh, which proved…inconvenient.) Annual bonuses were normal. Trips to the country regular.

We laughed all day in that place, even though we worked our butts off.

When I started seeing Donna and introduced her to them, they took to her immediately and folded her into the family. Donna used to ride the bus to and from her job and she got out early enough to come by the shop. She would come back at the point in the day when all the prints had to be dried. This was in the days, still, of what we used to call “real paper’—fiber-based, not resin-coated—and we used an enormous drum dryer. You’d lay a row of prints on the apron as it moved toward the polished ferrotyping drum, against which they would be squeegied. The drum, which was a good four feet in diameter, turned slowy and by the time they came round they would be dry and fall off into a tray. Donna would just come on into the back and start drying prints.

I think back to that time now and find a thick chord of nostalgia. Good times.

I worked there through an expansion that saw us making quite a bit of money. We started doing the b&w for several camera stores through Rainbo Color Lab. For a time I think we printed every black and white image sold in St. Louis. The roll-call of the stores is telling about how much has changed. Jefferson Camera, O.J.’s, Clayton Camera, Kreumenacher’s, Vazi’s, St. Louis Photo, Dicor, The Shutter Bug, Sappington Camera, Creve Coeur Camera, Schiller’s…

Of the bunch, I think Clayton Camera still exists and Creve Coeur and Schiller’s, all very much changed.

Earline had had her first bout with cancer in the mid-Sixties—uterine. When I went to work for them the second time, shortly thereafter, it came back as breast cancer. She fought that off. But then it came back again as a weird manifestation of lung cancer and that was when she began to lose. It metastisized and when it reached the brain she died. I occasionally still have dreams about her.

She’d started as a street photographer at 14. She was self-educated. When I went to work there in 1976, she was learning Russian. Just for the hell of it.

The demise of Shaw Camera Shop still causes a touch of bitterness. It didn’t have to happen. I’d offered a number of ways to change with the times, most of which, for reasons I won’t detail here but which were profoundly short-sighted and stupid, were ignored by the new owners. Little by little, customers went away and we didn’t replace them. Eventually, it just couldn’t be sustained.

Today if you go by there you’ll find it’s home to a lawn ornament/antique shop called Gringo Jones. They’ve gutted the insides, but, as I finally worked up the nerve to go through there last year, you can still see where everything was, a kind of archaeological trace. The liquor store is gone, too, but that had closed down while we were still open and was taken over by a botanical shop called The Bug Store, which is still there.

Irv’s Diner is long gone and where one of the gas stations was is now the forecourt of a research center owned by the Garden. Where the other gas station had been is a parking lot, also owned by the Garden. It’s a thriving neighborhood now.

Like many good things, I didn’t realize how much I liked working there until long after I didn’t anymore. I haven’t even touched on the wide range of characters we had for customers, a catalogue of unique people I doubtless mine in my writing. Many if not most brought smiles when they came in.

Occasionally, up on The Hill, St. Louis’s designated Italian neighborhood, you can still walk into a restaurant or a store and see a print we did hanging on the wall. One irony was that after two years of trying to break into publishing novels (and failing) I had to go back to a dayjob. I got one very quickly, at Advance Photographic, which was less than half a mile up Vandeventer from where Shaw had been. To my surprise and amusement, about half their black & white customers were my old customers. So for a brief time there was a bit of continuity.

But that’s gone, too, now. All that remain are a lot of photographs, memories…and a very substantial piece of who I am.