I’m taking time out (already) from all the rewriting I have to do to complain and restate a principle.

Here’s a lovely little bit of misogyny.

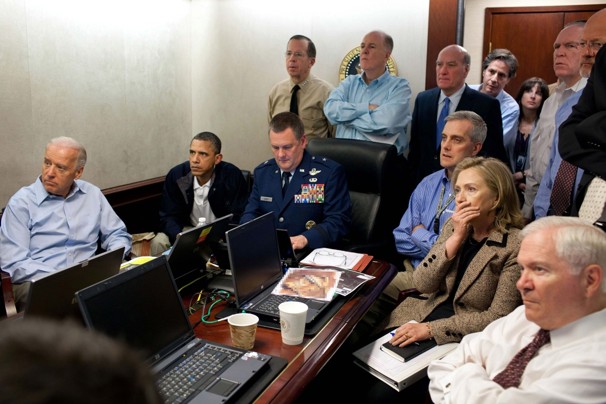

Read the article? A newspaper took the photograph of the ready room where Obama and his cabinet received the news of Bin Ladin’s death and photoshopped out the women present. For reasons of “modesty” they claimed. They then apologized but asserted they have a First Amendment right to have done this.

Inadvertently—and I am sure they didn’t think about this when they did it—they gave Bin Ladin a small cultural victory out of his own death. The religious view Bin Ladin asserted, supported, and fought for includes the return of women to second class status, to the status of property. By doctoring that photograph, the editors of Di Tzeitung tacitly approved this idea.

Modesty. Really? They erased Hilary Clinton and a staffer in the background. You look at the photograph in question:

Is there any way to look at that and perceive immodesty in the way we usually use the term? I don’t see any scanty clothing or alluring, over-the-shoulder glances at the camera. No legs, no cleavage, no hint of sexualization, which is what is normally meant by use of the term, even—especially—within the context of religious censure. This sort of attitude is intended as a guard against titillation and “impure thoughts”, but I’m having a hard time seeing anything like that here.

In fact, this has made clear what the real problem is and has been all along. Rules about “modesty” have nothing to do with sex and everything to do with power. Secretary of State Clinton—the Secretary of State of the United States of America, the most powerful nation on Earth, is a woman!—is a female in a position of power. She is the boss of many men. She is instrumental in setting policy, which affects many more men, men she doesn’t know and will never know. She wields power and that is what is feared by these—I’ll say it because I’m pissed about this—these small-minded bigots.

And in their effort to make sure their daughters never grow up with the idea that they can have power or any kind, not even in the say over what to do with their lives (because they don’t even have any say over how they dress, who they can talk to, where they can go, what they can aspire to), these “proper” gentlemen handed Osama Bin Ladin a final supportive fist bump of solidarity. “Yeah, brother, we hated the fact that you blew people up, but we really gotta keep these females in their Place.”

Cultural relativism be damned. I’m one hundred percent with Sam Harris on this. Subjugating half the population to some idea of propriety and in so doing strip them of everything they have even while hiding them head to toe and keeping them out of the public gaze is categorically evil. The fact that this is resisted so much by otherwise intelligent people—on both sides of the issue, those who perpetrate it and those who refuse to outright condemn it for fear of being seen as cultural imperialists—is as shameful as the defenders of slavery 150 years ago.

Now, at least, they’ve made it hard to miss. This wasn’t a photograph of some beauty pageant or a spread in Playboy or the Sports Illustrated Swimsuit Issue; this wasn’t a still from the red carpet runway at the Golden Globes or the lurid front page of a Fleet Street tabloid. No, this was a photograph of powerful people doing serious work and two of them do not have a penis. This is the issue—power. Women the world over have no say in their lives. They are wives, concubines, prostitutes, slaves. If they wish to change the way they live, they are forbidden, sometimes killed for their ambition. In many places still their daughters have their sex organs mutilated so they won’t ever fully experience sexual pleasure and, theoretically, never want to stray from the men who own them. They are denied the vote, denied a voice, denied even the courtesy of Presence in life. They are made background, wallpaper, accoutrements for the men who are set against yielding even a token of consideration toward the idea that “their women” are people.

People who happen to be women. People.

I am sick of this crap. I am sick of people who don’t understand the issue. I am sick of the tepid response among people who should see this as an unmitigated evil who won’t speak up to condemn it outright. By their reluctance to condemn they allow this sickness to grow in their own backyard. There are groups in this country who but for a few “inconvenient” laws would—and in some cases do—treat women exactly the same way. I am sick of the constant onslaught on family planning services and the idea that women should not be in command of their own bodies. I am sick of the feckless insecurity of outwardly bold and inwardly timid males who are afraid of the women around them, that if these women actually had some choices they would leave. I am sick of men who can find no better use for their hands than to beat women, no better use for their minds than to boast of their manliness, and no better use for their penises than to keep score. I am sick of women who are made to appear at fault for their own rapes because of the way they dress or walk or talk or because they thought, just like real people, they had a right to go anywhere they chose, free of fear. I am sick of seeing the human waste of unrealized potential based on genital arrangement and the granting of undeserved rights and authority based on the same thing. I am sick of being told by people who obviously haven’t stepped outside of their own navels that this is what god wants because some preacher or imam or shaman told them and they like the idea that there is someone who can’t say no to them no matter how abusive or failed they are as human beings. I am sick of seeing women pay the cost of men deciding for them what they should be.

For those of you who read this and agree, excuse the rant. Shove it in the faces of anyone who gives even lip service to the idea that women are somehow other than and less than males and that maybe a little “modesty” would be a good thing. Modesty in this context is code for invisibility.

Back now to our regularly scheduled Wednesday.