I am not given to setting out pronouncements like this very often, but in light of the last several years I thought it might be worthwhile to do so on the occasion of the 236th anniversary of our declared independence.

I don’t think in terms of demonstrating my love of country. My affection for my home is simply a given, a background hum, a constant, foundational reality that is reflexively true. This is the house in which I grew up. I know its walls, its ceiling, its floors, the steps to the attic, the verge, and every shadow that moves with the sun through all the windows. I live here; its existence contours my thinking, is the starting place of my feelings.

The house itself is an old friend, a reliable companion, a welcoming space, both mental and physical, that I can no more dislike or reject than I can stop breathing.

But some of the furniture…that’s different.

I am an American.

I don’t have to prove that to anyone. I carry it with me, inside, my cells are suffused with it. I do not have to wear a flag on my lapel, hang one in front of my house, or publicly pledge an oath to it for the convenience of those who question my political sentiments. Anyone who says I should or ought or have to does not understand the nature of what they request or the substance of my refusal to accommodate them. They do not understand that public affirmations like that become a fetish and serve only to divide, to make people pass a test they should—because we are free—never have to take.

I am an American.

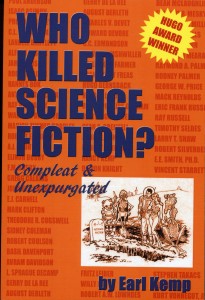

I am not afraid of ideas. My country was born out the embrace of ideas, new ideas, ideas that challenged the right of kings to suppress ideas. Ideas are the bricks that built these halls. I claim as my birthright the freedom to think anything, entertain any notion, weigh the value of any concept or proposition, and to take refuge in the knowledge that wisdom comes from learning and the freedom to learn is among the most hallowed and sacred privileges we have inherited as a country. The greatest enemy of our republic is the fear of ideas, of education, and by extension of truth and fact. Those who see no harm in removing books from libraries or diluting fact with wishful thinking and teaching our children to accept things entirely on faith and never question will weaken the foundations, damage the walls, and corrupt every other freedom they themselves boast about and then fail to defend.

I am an American.

I do not need to demonize others to make myself feel safe or superior or even right. I do not need to pretend that I am innately “better” than anyone else to prove my own worth. America was founded on the idea that all of us are equal in potential value. I do not need to oppress, undercut, strike, or otherwise impede others so that I can claim the dubious and ultimately meaningless label of Number One.

I am an American.

Sometimes I wear my sentiment on my sleeve, display my emotions at inappropriate times. I often side with unpopular causes, cheer those who aren’t going to win, get unreasonably angry over unfairness. I believe in justice and I don’t have any trouble with the idea of making an extra effort for people who can’t afford it for themselves. Other times I am stoic, even cynical. I accommodate a world-weariness far beyond the scope of my heritage. I do not believe in providence. Things will not just “work out in the long run” and the bad are not always punished and the good too often are crushed. I know the world doesn’t care and has no interest in level playing fields or evening up odds or anything other than its own ravenous acquisitiveness. It’s an uphill battle against impossible odds, but it’s the only one worth fighting, and I have an unreasonable belief that as an American I have a responsibility to help fight it.

I am an American.

I take a childish pride in many of the attributes and details of my heritage. We build things, we invent things, we have moved mountains, changed the course of rivers, gone to the moon, created great art, changed the face of the earth, broken tyrants on the wheel, and made the world yield. At the same time I am embarrassed at many of the other details of my heritage. We have hurt people unnecessarily, killed and raped, we have damaged forests, poisoned rivers, waged war when there were other avenues. I like the idea that I can work my way out of poverty here, but I hate the idea that we idolize the rich when they put barriers in the path of those like me just because they can. It’s not the money, it’s the work that counts, but sometimes we forget that and those with less must school those with more. That we have done that and can do that is also part of my heritage and I am glad of it.

I am an American.

I am an American.

I am not bound by ritual. Tradition is valuable, history must never be forgotten, but as a starting point not a straitjacket. Those who wish to constrain me according to the incantations, ceremonies, and empty routines of disproven ideologies, debunked beliefs, and discredited authority are not my compatriots, nor do they understand the liberty which comes from an open mind amply armed with knowledge and fueled by a spirit of optimism and a fearless willingness to look into the new and make what is worthy in progress your own.

I am an American.

I do not need others to tell me who I am and how I should be what they think I should be. I elect my representatives. They work for me. They are employees. If I criticize them, I am not criticizing my country. If I call their judgment into question, I am not undermining America. If I am angry with the job they do, I do not hate my country. They should take their definition from me, not the other way around.

I am an American.

If my so-called leaders send soldiers in my name somewhere to do things of which I do not approve and I voice my disapproval, I am not insulting those soldiers or failing to support them. They did not send themselves to those places or tell themselves to do those things. My country has never asked one of its soldiers to kill innocents, torture people, lay waste to civilians, or otherwise perform illegal, unnecessary, or wrong deeds. Politicians do that and they are employees, they are not My Country. Greedy individuals do that, and they are not My Country. No one has the right to call me unpatriotic because I condemn politicians or businessmen for a war they make that I consider wrong, nor that I am not “supporting out troops” because I want them out of that situation and no longer misused by the narrow, blinkered, and all-too-often secret agendas of functionaries, bureaucrats, and bought stooges.

I am an American.

My success is my own, but it is impossible without the work done by my fellow Americans. I acknowledge that we make this country together or not at all and I have no reservations about crediting those whose labor has made my own possible or condemning those who seek to divide us so they can reap the plenty and pretend they made their success all by themselves.

I am an American.

Which means that by inheritance I am nearly everyone on this planet. I am not afraid of Others, or of The Other, and those who would seek to deny political and social rights to people who for whatever reason do not fit a particular box simply because they’re afraid of them do not speak for me. I reject superstition and embrace reason and as a child I learned that this is what should be the hallmark of an American, that while we never discard the lessons of the past nor do we let the fears and ignorance of the past dictate our future.

I am an American.

I accept the rule of law. This is a founding idea and I live accordingly, even if I dislike or disapprove of a given example. If so, then I embrace my right to try to change the law, but I will not break it thoughtlessly just because it inconveniences me or to simply prove my independence. My independence is likewise, like my Americanness, something I carry with me, inside. The forum of ideas is where we debate the virtues and vices of the framework of our society and I take it as given my right to participate. Cooperation is our strength, not blind commitment to standards poorly explained or half understood. Because we make the law, we determine its shape and limits. The more of us who participate, the better, otherwise we surrender majority rule to minority veto, and law becomes the playground of those who learn how to keep the rest of us out.

I am an American.

Such a thing was invented. It came out of change, it encompasses change, it uses change. Change is the only constant and too-tight a grip on that which is no longer meaningful is the beginning of stagnation and the end of that which makes us who we are. Change is annoying, inconvenient, sometimes maddening, but it is the only constant, so I welcome it and understand that the willingness to meet it and work with it defines us as much as our rivers, our mountains, our cities, our art. A fondness for particular times and places and periods is only natural—humans are nostalgic—but to try to freeze us as a people into one shape for all time is the surest way to destroy us.

I am an American.

I do not need others to be less so I can be more. I do not need others to lose so that I can win. I do not need to sabotage the success of others to guarantee my own. I do not have to take anything away from someone else in order to have more for myself.

America is for me—

My partner, my family, my friends, the books I love, the music I hear, the laughter of my neighbors, the grass and flowers of my garden, the conversations I have, the roads I travel, and the freedom I have to recognize and appreciate and enjoy all these things. I will defend it, I will fight anyone who tries to hurt it, but I will do it my own way, out of my own sentiments, for my own reasons. Others may have their reasons and sentiments, and may beat a different drum. That’s fine. That is their way and we may find common cause in some things. This, too, is America.

“All colors and blends of Americans have somewhat the same tendencies. It’s a breed — selected out by accident. And so we’re overbrave and overfearful — we’re kind and cruel as children. We’re overfriendly and at the same time frightened of strangers. We boast and are impressed. We’re oversentimental and realistic. We are mundane and materialistic — and do you know of any other nation that acts for ideals? We eat too much. We have no taste, no sense of proportion. We throw our energy about like waste. In the old lands they say of us that we go from barbarism to decadence without an intervening culture.”

John Steinbeck, East of Eden

“There’s the country of America, which you have to defend, but there’s also the idea of America. America is more than just a country, it’s an idea. An idea that’s supposed to be contagious.”

Bono

“We are not afraid to entrust the American people with unpleasant facts, foreign ideas, alien philosophies, and competitive values. For a nation that is afraid to let its people judge the truth and falsehood in an open market is a nation that is afraid of its people.”

John F. Kennedy

“When an American says that he loves his country, he means not only that he loves the New England hills, the prairies glistening in the sun, the wide and rising plains, the great mountains, and the sea. He means that he loves an inner air, an inner light in which freedom lives and in which a man can draw the breath of self-respect.”

Adlai Stevenson