Some people just get in.

In this instance, though, the process was years at work.

Harlan Ellison died on June 28th, 2018, and I have been off-balance, riled, and melancholy ever since I saw the first notice, at work, doing something else on-line. It had been coming for a while. He was not well. He was never going to “recover” from the last few years. A stroke had wreaked havoc with him, although it had left him with access to all his faculties. This was expected. Nevertheless, it came as a shock, if not a total surprise, and the aftershocks have been working through me ever since. This one hurts. Deeply.

How, exactly, did this happen? I did not know the man so well. If I had to guess, I would say we had spent less than a week of actual face-to-face time together. We had spoken on the phone a total of maybe twenty hours in a number of years. I’d written him a few letters and he had written back. And yet, at least on my part, I counted him as a friend. I know that can happen, that people can know each other a very short time and somehow create a connection which, with other people, would ordinarily take years to build. It may well be only on my part, but I don’t think so.

How, I ask again, did this happen?

Well, there was this review I wrote about the documentary, Dreams With Sharp Teeth. But it didn’t really start there.

Back in my youth, I used to read all the SF magazines. From time to time I’d come across a story that stood out. Zelazny, Silverberg, Tiptree. Those kind of stories. Among them were fey pieces by this guy Harlan Ellison that troubled me. They troubled me because while I read them eagerly and felt moved by some of them, I suspected I didn’t really “get” them. These were not like most of the other stories. In fact, they weren’t like any of them, really. And they bothered me. So much so that at about age 15 or 16 I swore off them. If I stumbled across a Harlan Ellison story, I avoided it. I was uncomfortable with them, they disturbed me in ways no one else’s work did.

And I more or less forgot about him.

I was unaware of scenarists back then. When the credits rolled on a tv show or movie, I never paid much attention to the Written By. Or much else other than who was acting in it. I was dimly aware that the Star Trek episode which has subsequently come to be regarded as the best of the original series was different. For one thing, when I saw it the first time I was startled by a curse word. “Let’s get the hell out of here,” Kirk says. That was practically unheard of on television then. That “hell” stood out.

But what did it mean? The rest of the episode stuck with me more clearly than most of the other episodes, but then time passed and everything else piled on top, and I forgot.

I had no knowledge of Fandom then. I was ignorant of that world, so the controversies being generated by this guy who had written stories that bothered me enough that I avoided them were unknown to me. The next time his name crossed my awareness was in the pages of OMNI when I read two things. One was a short story, called On The Slab and the other was a profile of an attempt to turn Isaac Asimov’s I, Robot into a film, and Harlan Ellison was going to adapt it. Harlan Ellison. I remembered that name. Why did I know that name? Oh, yeah, he wrote those weird, unclassifiable things that bothered me. Huh.

In 1980 I met my partner, who read the rather malformed things I’d written and encouraged me to try to publish them, and suddenly I was fully invested in this science fiction thing. Friends told us about conventions and we started going. We began meeting people. Joe Haldeman, Phyllis Eisenstein, George R.R. Martin, Rob Chilson, Vic Milan, C.J. Cherryh. I started submitting stories and I began paying closer attention to the magazines again, trying to divine the secrets of writing this stuff. The first convention we went to was Archon 6 and we heard stories about the one and only world science fiction convention that had been held here and Harlan Ellison figured prominently in relation to it. We listened to these stories and wondered, “Who is this guy?”

In the 1980s a new publishing line came out, Bluejay Books, and they reissued Ellison’s work with marvelous new covers, and I bought them and started reading them.

And suddenly they were not off-putting. Maybe I had grown into them. Maybe it required more of me than I had at 12 or 14 or 16. Maybe I was paying attention to Other Things. Whatever the reason, I tore through them, unable to get enough, amazed and awed and startled and terrified and intimidated and thrilled. I wrote a review of them (which never got published) which involved dinner of crow. Harlan Ellison’s work suddenly ranked alongside Bradbury, Sturgeon, Zelazny. I’d missed this way back when, I hadn’t understood, but it filled me up then. It might have been that I was in the process of trying to do this thing and was open to influences in a way I had never been before.

During this time, we’d become friends with another writer, Ed Bryant, who was one of Harlan’s best friends, and we heard more stories. At our first worldcon we got our first look at the man himself when, at L.A.Con II he made a surprise appearance in order to honor his first editor on stage during the Hugo ceremony. We picked up some of his nonfiction there and I became acquainted with that side of him.

Gradually, almost glacially, we became Aware. We found out about the Enemies Of Ellison (what?) and his involvement with Clarion (the workshop) and started hearing about his public contentiousness, the dispute with Roddenberry, the activism, the rumors, the extremes he generated in people. No other writer seemed to do these things or spark this kind of response. Piece by piece, a portrait assembled, but how could you trust it.

It’s fascinating sometimes to realize how much information one can accrue by means, vectors, and sources one is often completely unaware of. We saw him again in 1986, in Atlanta, and spent about four hours in an auditorium listening to him, both solo and then, when he ran over, in a panel which had been physically moved to that auditorium in order to have Harlan on it. We had had an exchange of dialogue that day over a book I’d bought in the dealers room (the only time a writer told me I should get my money back for a book with his name on it), and somehow we knew that he had found his soulmate, Susan, and she was with him, and Donna opined that it seemed she had calmed him somewhat.

How did we know that?

I applied for Clarion the next year and was accepted into the 1988 class. I had a book, Phoenix Without Ashes, by Ed Bryant and Harlan Ellison. Ed had signed it for me years before. Ed happened to be in town one weekend to help a mutual friend of ours move. He lifted that book and sent it to Harlan for his half of the autograph. (Ed was a wonderful, kind man.)

And somewhere during that time, he had become Harlan. Just Harlan. To my knowledge, he’s the only writer I know of who is recognizable by his first name, at least the only writer of fantastic fiction so known. But how did that happen, that somehow a certain presumption of intimacy had occurred? Except for that one occasion in Atlanta, we never never met, did not know each other. (Not that unusual, though, many people who have never laid eyes on him call him “Harlan” as if they know him.)

More stories, more essays. He was by then a regular part of my reading.

Clarion happened. I began publishing. I rarely thought about “Harlan Ellison” unless I came across a new story or new collection, but Harlan had become part of a gestalt associated with my writing, a background presence.

We heard about the heart attack.

Then in 1999, Allen Steele suggested we come to Massachusetts for Readercon. Harlan was going to be guest of honor. He and Allen were buddies. We could finally meet.

We went. It was an incredible weekend. I had a chance to sit and talk to Harlan, to watch him, to see what all the fuss was about. And to hear him read aloud. That was a treat. Few writers are good public readers, but Harlan was incredible.

Allen introduced us. Harlan was talking to Gene Wolfe, whom we know slightly, and Allen brought me up and said, “Hey, Harlan, I’d like you to meet my friend, Mark Tiedemann.” Allen then proceeded to recite a list of my publications. I am perversely shy about that, more so then, and I cut him off with a self-effacing, “Yeah, I’ve all over.” Harlan, without missing a beat, said “Oh, yeah? What’s it like in Tuva?” My brain skipped a beat. One of the few times in my life under circumstances like that it caught up and somehow pulled an answer up. “Very flat and cold, but if you’re into monotoned nasal music, they’ve got a great scene.”

Harlan said nothing for about five seconds, then cracked up, stuck his hand out to shake mine, then said “When were you last there?”

But my powers of repartee deserted me then and I had no reply.

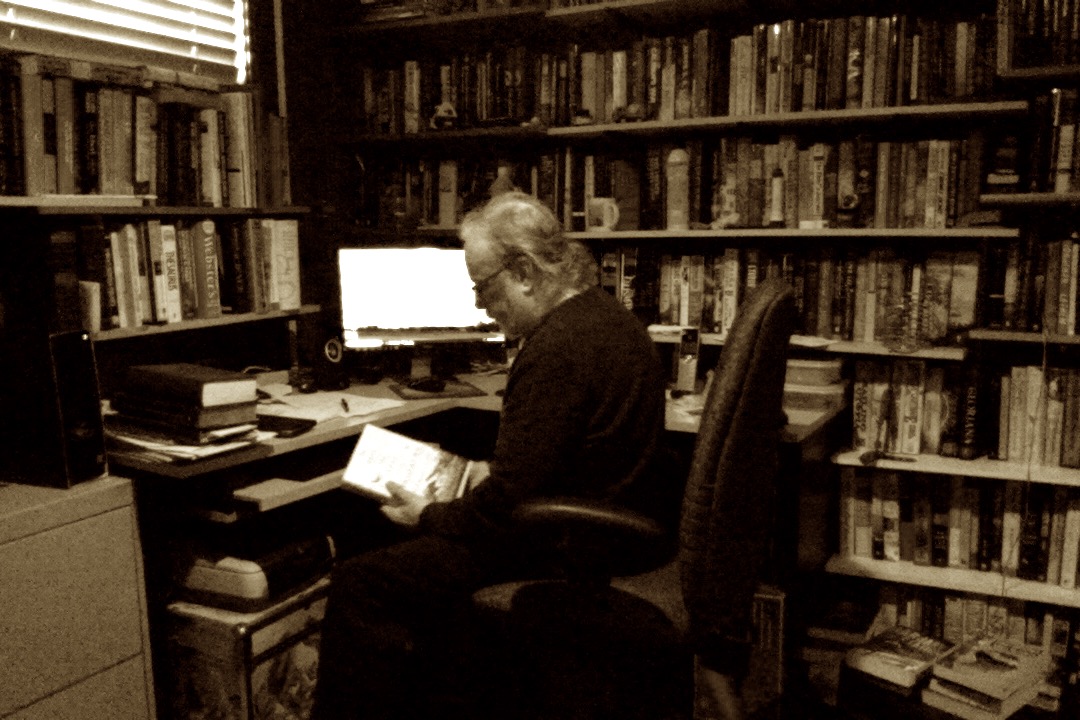

Saturday night that weekend, I was wandering the hotel late. About to give it up and go back to my room, I waited before the elevators. The doors opened and a crowd poured out, led by Harlan as they made a beeline for one of the function rooms, which the hotel opened up so they could continue the party which had gotten them booted from a room on the fifth floor. I was swept up in the throng, carried into the room, and ended up sitting two down from Harlan, who was regaling his audience still with jokes and stories. (Somewhere there exists a photograph of him that night and you can see me, sitting, I think, beside Warren Lapine, who is right next to Harlan.) It was one in the morning and after a grueling day Harlan was still On. He seemed to vibrate from the stress and tension, but he was delivering his 110%.

After that, we had no contact. I pursued (desperately) a career that never got off the ground and thought not at all about any relationship with Harlan Ellison.

Then the documentary came out. Dreams With Sharp Teeth is a singular work. It may not be very complete history but it certainly gives a vivid picture of the person. I wrote a review of it and posted it on a blog site I’d been guesting on for a few years. (I put it on my blog, too, but I thought the film deserved a signal boost that might do some good, so it went to Dangerous Intersections.) A month or so after it appearance, the webmaster emailed me to say that he had been contacted by someone claiming to be Harlan Ellison who wanted to talk to me, could he get either my phone number or let me know. My friend was suspicious so passed it by me without responding.

Well, it was from Harlan. His phone number was attached. I thought, you’ve got to be kidding me.

I called.

Harlan wanted to personally thank me for the review. He thought it was insightful.

From that point on, we called each other occasionally. Never a lot, a few times we spoke for over an hour. He offered once to intercede on my behalf with an editor. I thanked him but declined. I think he respected that.

And then came Madcon in 2010. We spent a goodly amount of time with him there. I honestly did not know what he thought of me, but he made himself available, and during what was a very hectic weekend for him, he was generous with his time.

We thought we would never see him again.

Then came the stroke.

And then the whole Archon affair, of which I’ve already written about.

The last time I saw Harlan was the morning he was leaving for the airport from the Collinsville Doubletree. Donna and I had picked Susan and him up the previous Thursday, others of his friends were taking him back. He had been using our transport wheelchair all weekend (long story, never mind) and this was where he had to leave it. Donna hugged him, I hugged him, he got into the van. The door closed. He looked at me through the window and put his hand on the glass, splayed out. I was a little startled, but I reached up and pressed my hand to glass opposite. He smiled and gave a small nod.

We spoke on the phone a few more times after that. Short conversations. He said he had had a wonderful time at Archon. We needed to come out to see him, to see the house (the wonderful house, Ellison Wonderland). We had no other reason to go to L.A. though, so we prevaricated. Then it was announced that the Nebula Awards would be in L.A. in 2019. We could attend and see Harlan and Susan again. It would work. A bit pricey, but hey. I was planning to call him to tell him. I was going to.

I should have.

Somehow, between the stories (and the Stories) and the few encounters, and then the all-too-brief time when we actually knew each other, he got in. His passing hurts. It’s strange to miss someone you knew so short a time, even if in some ways it was a lifetime.

Harlan Ellison was a singular person. Enormously talented, voracious in his approach to life, generous, unpredictable. Harlan, I think I may say, was a friend.

I miss him.