2013 is shaping up early to be one of those singular years in which people will be asked “Where were you when…?”

Two things of note at the moment, both of which have the slimmest of connections—or maybe not, depending on your perspective: this is the first largely popular effort in support of gun control since the late Sixties, at least rhetorically, and, if the polls are to be believed, demographically; and the first resignation of a sitting pope since 1415.

Connected? In terms of the kind of faith some people bring to certain givens, perhaps. But in both cases, core ideologies are being challenged by external pressures that have grown so great as to impose change.

External pressures? In a word, reality.

Let’s start with the Pope. It came as a shock even to the non-Catholic world, his resignation. After eight years, he’s had enough. He is an old man—Joseph Ratzinger was born in 1927—and aside from everything else that is not an easy job. He became pope during a time of internal strife and public ignominy over the child sex abuse that has been an ongoing problem for the Catholic Church for decades now. What, from all I can see from the outside, he tried to do was continue to reassert a traditional model of Catholicism on a body religious that has been fractured and mutating since Pope John XXIII and his Vatican II reforms. Every subsequent pope since has been trying to put certain genies back into a bottle that is cracked if not broken.

The failure of the Catholic Church to deal with the abuse scandal, however, points up another problem that predates even John XXIII and goes to the image the Vatican has of itself, namely that it is in some very real way a separate authority from the secular world in which it operates.

John XXIII was in very significant ways trying to address that very issue through Vatican II, namely that till then the Church had held itself so apart, ideologically and philosophically, from the world that it did not feel obligated on any level to admit to changes in that world which had a bearing on how it conducted itself.

I go on a bit about John XXIII because of the ironies nascent within his reign. See, he was the second Pope John XXIII, and I think it many ways he chose that name because the first of them had been technically an antipope. That’s relevant in this instance because of the media fillip about Ratzinger being the the first pope since Gregory XII to resign—and Gregory XII reigned as pope simultaneously with the first John XXIII.

As well as simultaneously with Benedict XIII.

Three popes? This was at the end of a century or more of intense change throughout Europe, culminating in the Western Schism (1378 – 1417) which came to a close when all three of the sitting popes—one in Rome, one in Avignon, one in Florence—abdicated and a new election was held and Martin V became pope. The question central to orthodoxy, of course, is how could such a thing possibly occur since by convention popes are elected at the influence and direction of God.

The other part of this has to do with the resignations themselves, which were hardly voluntary, but coerced. John XXIII himself was imprisoned afterward and had to be ransomed. The last pope to decide for himself to step down was Celestine V, who quit the job five months after having it thrust upon him in 1294 when he realized how inept he was politically. The man—Pietro Angelerio—had been a monk and hermit and found himself, at age 79, impotent to have his decrees enacted or enforced. He quit. (Dante placed him in the antechamber to hell for cowardice, because the one who followed Celestine V was Boniface VIII, whom Dante places firmly in Inferno.)

None of this reveals divinity but political deal-making and squabbling. However, by tradition everything to do with the papacy becomes the direct will of God (who moves by mysterious ways we are told).

Clearly, though, the actions of the Vatican since the second John XXIII bear all the hallmarks of a secular state that has turned conservative and is trying to reimpose some kind of authoritarianism upon an increasingly willful populace who have problems Rome has been unwilling to admit exist much less attempt to address in any concrete way. It has all come to a head with the child sex abuse scandals.

To be clear, no one except the least informed suggests that this is a problem solely of the Catholic priesthood. The fact is, in terms of numbers, priests who do this are no more numerous than in any protestant denomination—in fact, there may be a bit less—and the numbers aren’t high. Not in terms of priests. In terms of victims, there may be considerably more than in other denominations because of the internal policies of the Catholic Church, and it is there that the distinction has force. Because the Church, even when they found out, left these priests in place, sometimes for decades, and imposed its authority on the victims to silence them, first by playing on their Catholicism and then later with threats or pay-offs. In a protestant church, if a minister is found out doing this, the police are called and he’s arrested. He is handed over to the state authorities because he has committed a crime. Rome does not recognize such authority with regards to its officers (priests). This is, for them, an internal affair, and they will handle it, thank you very much.

Except the world has changed and this is wishful thinking on their part. Yet, they stick to their core ideology in face of this changed world, trying to pretend that they still represent, in their practices, something relevant. They may very well, but not at the expense of ignoring what is around them.

The Catholic Church long ago constructed a narrative in which they try to live, one which serves the ideology that defines them.

Likewise, organizations like the NRA are currently constructing a narrative which serves the ideology that defines them. Like the Church, they have elected to ignore reality and focus on a core set of premises which may at one time have served a purpose but which have become ever more problematic in a world that no longer functions the same way.

There is a faith element to both situations that is striking in how transparently at odds they are with the world we live in, but it is a faith held primarily by those who are insisting that their vision is the correct one in opposition to the context in which they operate.

The answer to gun violence is more guns? Really? The answer to pedophile priests is continued immunity from prosecution and more confidence in the institution that is shielding them? Really? The answer to these is to do exactly the opposite of what is being asked for, indeed demanded, by the people who are feeling most victimized by dysfunctional practices?

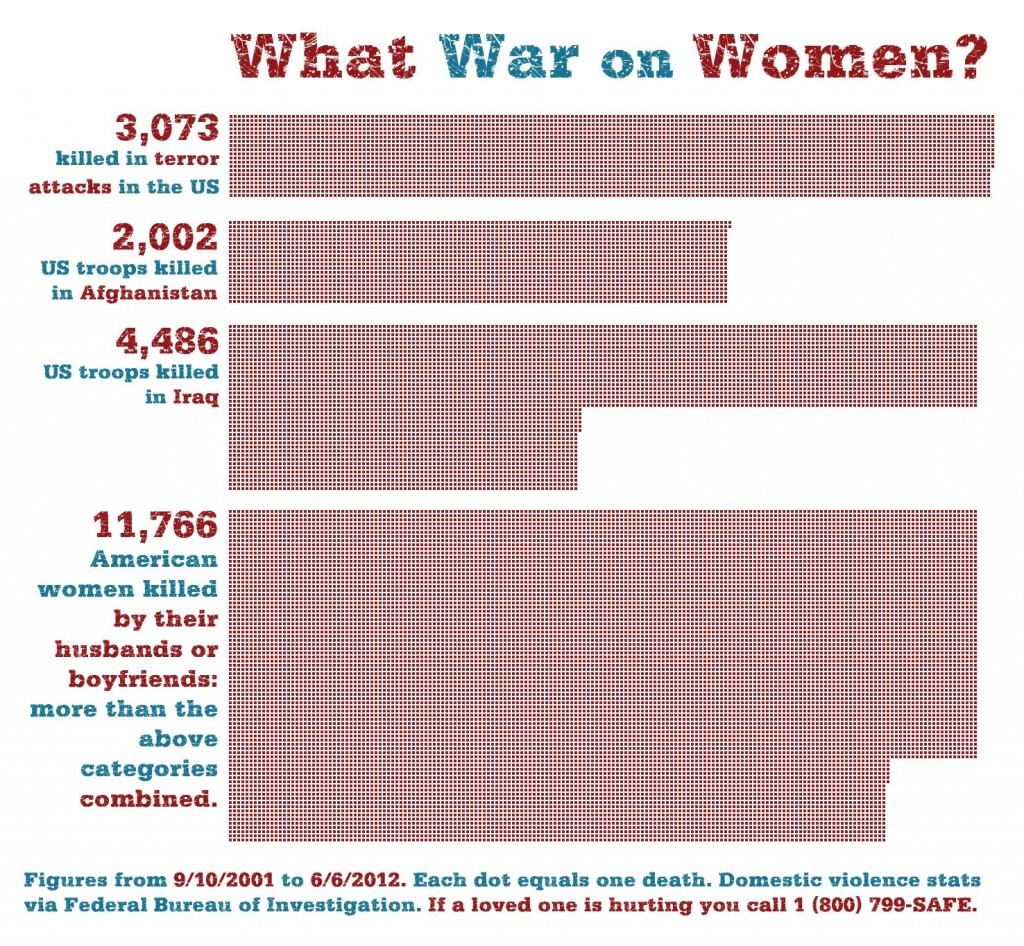

What is obvious in both cases is that we are seeing widespread retrenchment and a hardening of ideological bastions against an assault that by any metric should be viewed as an opportunity for better and more constructive communication and involvement. They are both responses to perceived threats. The demand for accountability for child abuse by priests is viewed as an attack on Church authority instead of what it is—a demand for justice. The demand for better controls on firearms is viewed as an attack on a presumed right of personal defense (and an implicit right to counter government abuse by violence) instead of what it is—a demand that people who should not have access to deadly force should in fact be kept from such access.

But furthermore, on both sides, there is a growing consensus that there ought to be a space in which safety can be taken for granted not gained by a willingness to assert personal force. People want to know, with surety, that they can go to church and be safe, because that’s what church means. They also want to know they can live in their neighborhoods and send their kids to school in safety and not have to worry about being ready to draw down on some nutjob gunning for an apocalyptic crescendo. These are not just reasonable expectations, they are in large part what most people mean when they think of civilization. It is not right that they be made to feel somehow marginalized because the institutions on which they should be able to depend are willing to sacrifice civilized behavior to defend an authority that, frankly, is not even under threat.

But when every comment, criticism, or conversation is seen as just such a threat instead of an attempt to find common ground, it is obvious that those defending the core ideologies are doing so with more and more irrelevance to the world around them.

The NRA started out as an educational organization and when they did that they were very good at it and very effective. The organization was a good citizen. But bit by bit their mission mutated from education to advocacy and their tone has become more and more stridently absurd, all in reaction to the boogie man of tyranny and at the expense of a valued place at the table. The gun, for them, is becoming more important than people and public safety. All because they have been constructing a narrative based on a false premise of an American past more faithful to bad Westerns than actual history.

We’ve heard the motto more and more lately, an armed society is a polite society. This is patently false to anyone with a modicum of historical grasp. Some of the most polite societies have been unarmed and some of the most violent and crude have been armed to the teeth. There is a reason dueling was outlawed from the 15th century on by every country that aspired to be called civilized. Might does not make right, not in the arena of public discourse—it only makes for arrogance, tunnel vision, and inequity. Because right cannot be asserted by force, whether physical or intellectual. Right must be demonstrable in and of itself, through actions and a willingness to admit error.

Something the Catholic Church has, in fact, been learning to do, but which it still hasn’t quite gotten a good handle on.

There is another way in which the two things are connected. Some genies are too big to put back in their bottles. John XXIII started a series of reforms designed to bring the church into sync with the world, to meet the needs of people in the modern age under circumstances that have unquestionably changed. The Church seems to have been trying to deny this vision ever since, by electing ever more conservative popes who toe ever more conservative lines (the last reformer, John Paul I, met with a very early demise, and there are valid questions to be answered about the circumstances). They are fencing with schism as a result and have certainly paid a price in attendance. Likewise, the sheer quantity of firearms in this country and the culture in which they exist represent a genie of a different sort, just as unlikely to be put back in a bottle. The landscape has changed. In that sense, the gun lobby is defending something that doesn’t need defending. It is what it is. A new approach is required. A reform of the culture. We need desperately to tell ourselves a new narrative. Because without that, all we’ll have is more of the same.