On my own this weekend, with the dog, working on rewrites. For the time being, a little cloud-gazing for you.

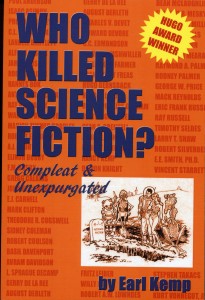

I just finished skimming through a fascinating little bit of fannish history, Earl Kemp’s Who Killed Science Fiction? Fannish in the sense of science fiction fandom. It has a rich and varied history and the concerns within the genre are as fraught with angst, ennui, and ambition as any literature.

I am always a bit bemused when I read about this sort of thing, because I came into science fiction through the rotary rack at my local drug store. (Literally—Leuken’s Pharmacy, on the corner of Shenendoah and Compton, a good old fashioned drug store with a soda fountain, a magazine stand, and two circular racks for paperbacks, two blocks from my house.) I had no idea about where these books came from, who wrote them, how, not to mention the whole publishing industry and its workings. I used to think authors were “gray eminences” who occasionally deigned to write a new book and “gift” it to the public. The notion that they did it for money or to meet a contract deadline or anything so mundane never occurred to me. It was a wholly mysterious process, with arcane rituals and secret rites.

I am always a bit bemused when I read about this sort of thing, because I came into science fiction through the rotary rack at my local drug store. (Literally—Leuken’s Pharmacy, on the corner of Shenendoah and Compton, a good old fashioned drug store with a soda fountain, a magazine stand, and two circular racks for paperbacks, two blocks from my house.) I had no idea about where these books came from, who wrote them, how, not to mention the whole publishing industry and its workings. I used to think authors were “gray eminences” who occasionally deigned to write a new book and “gift” it to the public. The notion that they did it for money or to meet a contract deadline or anything so mundane never occurred to me. It was a wholly mysterious process, with arcane rituals and secret rites.

Nor were all books created equal in my mind. For some reason—purely aesthetic—I early on decided that the best science fiction, the stuff with true weight and merit, was all published by Avon. They did Asimov’s magisterial Foundation Trilogy, after all, and that was Significant Literature! They put out a lot of Zelazny and some Silverberg.

But I knew nothing about fandom. Occasionally I’d see a notice in the back of one of the magazines I read—If, Galaxy, Amazing, Fantasy & Science Fiction, Vertex, Venture—for a convention somewhere, usually a “World Science Fiction Convention” (!), but I thought they would necessarily be by invitation only (where all the gray eminences met to determine the future offerings, etc) and I’d never go to one.

Kemp’s little tome is the result of a survey he sent out around 1960, asking the title question, among others. Damn. I started reading the magazines regularly around 1963 or ’64, so if already in 1960 there was concern over SF being dead, then…

Most of the seventy-odd respondents thought SF was not dead at all, but was in the doldrums. This was right after the so-called Golden Age has ended (roughly between 1938 and 1954 or so) and there was apparently a sense that the Next New Thing hadn’t arrived yet and maybe it wouldn’t. It was right on the cusp of New Wave and a few years before Campbell changed the name of Astounding to Analog. There’s the sense of people sort of milling around, waiting for Something To Happen.

Well, it was five years before Dune and seven years before Dangerous Visions, two books that arguably changed the field. In a way they represent two extremes, the last great epic of traditional SF and the compendium of All The Wild Shit coming down the pike. (Both books are almost continually in print to this day, and while Dune has become more a media and franchise phenomenon, Dangerous Visions and its sequel is still a touchstone for serious literary study and the taking-off point for the changes in approach and trajectory that drove everything until Gibson, Sterling, and Cyberpunk worked another set of changes on a field that has always been as good as its most recent thing.)

The general consensus throughout the responses was that magazine SF was not dead (and there did seem to be an over-emphasis on the magazines, which at the time were still seen as the major outlet for SF. Book publishers had not yet really crowded into the field as they did by the end of the decade, although some were putting out quite a lot, like ACE) but it was sick as hell. I’ve sat in on similar conversations over the last three decades of my own involvement in fandom and I was struck reading this by the similarity in tone and even in content of the arguments. (Horace Gold, editor of Galaxy, thought everything was fine except for too much psi.)

Kurt Vonnegut chimed in with a particularly venomous assault, that not only was it dead but he would be glad to help find the corpse so it could be properly buried. He wrote a note to Kemp later apologizing and blaming his attitude on his isolation from the field. Vonnegut made his bones in SF and took many opportunities to diss it because he didn’t want to be regarded by the critics—and therefore his potential audience—as a hack. Fair enough, but sometimes I wonder if something else was going on there. He could have distanced himself without pissing all over the whole genre. Or maybe not. I have to bear in mind that the critical arena is not what it was then.

The last section of the book contains revisitations some 20 years later, when science fiction was going through an enormous boom. Some of the pessimism of the earlier responses had to be explained.

A lot of of them credited Star Trek with the “revival” of science fiction. It did bring a much larger audience into the field. It did open the door for many of those new readers to discover that, as good as they thought Star Trek was, the stuff between two covers was much better.

That all changed again in the 80s with the massive upsurge of Fantasy, all, in my opinion, in the wake of Star Wars, which did something very similar—brought many tens of thousands of new fans eagerly into the field. But in this instance, a different realization occurred that led to a collapse of science fiction. Instead of discovering that the material in the books they were now buying was better than Star Wars, they found that it was utterly different—and that they really didn’t like it.

Star Wars—and I’ve said this before, often—is not science fiction (even though Lucas rather hamfistedly and stupidly tried to retrofit it as science fiction in the “first” three movies) but heroic quest fantasy in space. Or, simply, Fantasy in Skiffy drag. Audiences went from this to the less reifying work of writers like Brin, Bear, Clarke, Benford, Cherryh, et al and it must have been like a cold shower. Science fiction requires thought, analysis, its virtue is in the explication and championing of reason, logic, and science, and while there are heroes aplenty in SF there’s not a lot of destiny or “born to the throne” heroes who just Are.

As fast as they blew up the SF bubble, they left it for all the Tolkein clones that began to dominate the publishing field by the late 80s and still command a hefty market share.

Science fiction, it seems to me, has always been a minority taste. It appeals to people who also find science appealing. It has always had a fairly solid core of supporters and as a percentage of the publishing market has remained fairly constant, with certain boom times punctuating a more or less steady, dependable foundation. Science fiction offers marvels, of course, but they are, the best of them, marvels still grounded in an idea of reality. And reality is tough. It takes work to survive and thrive. A good sword arm won’t do you much good when a meteor has holed your ship and all the air is leaking out and you have to figure out how to fix it. Orbital mechanics couldn’t care less that you’re of the House Royal as your ship starts spiraling down to a nasty end because you didn’t do the math right for re-entry into atmosphere. Science fiction says “Yes, the future can be wonderful—but it will still be Real and you’ll have to deal with it the same way you deal with what’s real now.”

So, who killed science fiction in my opinion?

Lot of assumptions in that question with which I do not agree.

Years ago I got to have a long talk with the illustrator Kelly Freas and we found common ground in believing that black and white is a superior artistic medium to color. I’m a sucker for fine b&w drawings and my first love in photography was Ansel Adams.

I pulled out some old proof sheets, from our road trip back in 2001, and started scanning in a few negatives. These were 120 format, 2 X 2, which I like for the sharpness and lack of grain. Sometimes I still miss having a darkroom, the smell of the chemicals, and the magic of watching an image appear in the tray, little by little, growing before my eyes, details filling in. As much as I’ve been enjoying working with digital—and certainly I don’t really miss the messiness of traditional photofinishing—I wonder where kids find the “magic” of that first print.

I’ve been doing more color with digital as well and I need to shift that back to black & white. There’s a clarity, a “cleanness” to black & white that color never quite achieves.

I thought I’d share a couple of these with you today.

One thing working with these has given me, though, is an urge to do that trip again. I got some great shots and I’ve done far too little with them. I could spend the next two years doing nothing but scanning and processing the photographs in that file.

But I’d start with the black & white first.

Have a good weekend.

I am inspired to write this because of two things, one significant, the other merely annoying. I start with the merely annoying.

I’m hopelessly behind the curve tech-wise. I can barely make my way around the internet, and if something melts down on my computer I run in panic from the room wondering who to call to fix it. Partly, this is a result of being too busy the last three decades to keep up, partly it is a response to the incessant demands of the digital marketplace to constantly, eternally acquire the latest gadget, the newest thingie, the most recent incarnation of Nousmasticator 3.1, all of which is both time consuming to install and maintain and often pretty damn expensive. As a child I remember jokes about people who had to buy a new car every year, which later morphed into the “planned obsolescence” of Detroit product that required a new model after sixty thousand miles, but the auto industry never had a thing on the computer world. I resent it. Perversely, I’ve refused to keep abreast. This is classic surgical removal of probosci to articulate displeasure with one’s demeanor.

And it’s petty.

This morning a notice for an available upgrade appeared in the hopper of my blog and I haplessly accepted it. My blog promptly disappeared. After messing with this, on the phone and by email, for over an hour, I discovered that for some reason the upgrade trashed the files of the existing blog template, rendering it unusable. Since my system indicated that I still had the damn thing in my archives, I was unable to upload a new version and had to install a brand new theme. You’re looking at it now. And actually I kinda like it.

But that’s not the point. I shouldn’t have had to go through all that nonsense. I do not need another little Gordion knot of dyspeptic resentment toward the nature of the modern world binding itself into my psyche along with all the other little bits of tedious, petty anoetic effluvia cluttering up my memorative gestalt.

Which brings me to the other inspiration for this piece.

Recently, I received in the mail volume 6 of Harlan Ellison’s On The Road lectures. (An aside, briefly, to suggest you avail yourself of some of these, especially if you are an appreciator of the spoken word and good repartee—they are collections of Harlan’s public presentations over his long career and they are a delight. They are available by mail through here.) The liner notes of this one comprise a longish essay by Harlan in which he discourses on one of his attributes.

He is, he claims, a petty man.

This is also part of his acceptance speech for the Grand Master of Science Fiction Award, given him by SFWA in 2006 (included in this collection, along with Neil Gaiman’s excellent prefatory words). He’s copping fair on a characteristic he expresses some regret over, some wonderment about, a puzzle, a burden, an inextricable part of his nature.

My initial reaction was big deal, aren’t we all? Then I thought he might have been laying the groundwork for distancing himself, the man he is, from the work he has done, leaving behind nothing unadmitted and owned up to for future biographers, chroniclers, and literary archaeologists (and, let’s face, academic parasites) to “discover” and base a “reassessment” on which will completely miss the point.

In one of the best author biographies I’ve ever read, Julie Phillips, in her chronicle of the life of Alice Sheldon, aka James Tiptree Jr., manages to do something rare and remarkable, which is to study the source of fiction without suggesting that the fiction is useful for some kind of psychoanalysis. She examines the forces in Sheldon’s life that led her not only to adopt a deep cover pseudonym from which to write but to write the kinds of stories she did, but at no point does she suggest the stories are what they are only because Sheldon was troubled, flawed, paranoid, suicidal, whatever. In Phillips’ hands, the stories are something apart, works of art, certainly created out of the life that shaped them, but once created took on separate status, to be regarded on their own terms and not taken apart or essentially deconstructed based on who Sheldon was (or who we might think she was). Sheldon wrote the way she did out of her own essence, true, but she nevertheless created something distinct from herself that should be taken on its own terms, for what it is, not for who made it.

Harlan has as vivid a public presence as himself as his work does as itself. It’s evident, reading over his essays, that he has mined himself for the substance of his stories, for the raw matter that he then shapes into dramas. It is legitimate to say that he assays autobiographical themes in many of his best stories, even as it is a mistake to see the stories themselves as autobiographical. He’s done what good artists do—lived, reacted, felt, put the result into his art, saying to us “I am human, I have felt these things, witnessed these things, concluded these things, and because you, too, are human you will know what I’m saying to you.” He is not saying in his fiction “This is who I am” but more importantly “This is who we are.”

But because we live in a culture obsessed with celebrity and the insistent need to bring everyone down to the level of those who prance shamelessly upon the stages of talkshows where their least indiscretion is blown up into a life-changing, earth-shaking moral verdict, it is too often the case that biography trumps creation in the mind of the Public Beast. Separating the artist from the work is a problem, because the work, while inextricably part of the artist, is not the artist. The work is the work.

With that in mind, I read the essay thinking that this was something Harlan was trying to do. “I know who and what I am and I’ll tell you about it here and now so you don’t have to let its discovery later poison the work I have done.”

I’ve since reread the essay and listened to more of the CD and I don’t think that’s what he was doing. At least not primarily.

He relates an instance of coincidental karma concerning another writer and cosmic payback. Within the context of his theme—I am a petty man—he suggests that petty gets what petty gives. It is perhaps an examination of the conundrum some people are that the more they have, the more they succeed, the higher up whatever ladder they’ve been trying to climb they get, it is the little things that never let them fully be as complete as the work they do.

We’re all petty. Not so much that we do petty things, but that we have petty thoughts and petty concerns. Myself, I have a roomful of memories in my hindbrain of embarrassing, unkind, thoughtless things I’ve said and done that I just can’t seem to be rid of. Most of the time I don’t think about them, but every once in a while, when I’m least expecting it, one of these damn things pops up in my mind and taunts me with the fact that there is nothing I can do to change it! It happened, it’s done, it’s part of history, and I can never undo it. I obsess over them for a while, imagining myself behaving differently, using different words, taking a different course, or just paying closer attention at the time. I’m a writer, I can imagine whole novels of better responses, better motives, better outcomes.

But there’s nothing I can do and apparently I can’t even forget them.

Like time and motion studies, I analyze them for clues of my essential cluelessness, which I will also never be able to change, because I didn’t understand it at the time. Or maybe I did but I still didn’t think it was a bad idea. Or I knew, but couldn’t figure out how, at the time, to avoid the mess it was about to be. I rework them in my head, trying vainly to optimize the therbligs of my past and utterly helpless to do so.

I consider my continual obsessions with these things petty. The events themselves were petty, inconsequential in the greater scheme of my life, and I imagine that the other players may well not recall them at all. But I can’t let them go.

They do turn up in my fiction. Not the events themselves, usually, but the fact of the pettiness, the nature of the embarrassment or resentment or anger or stupidity.

And it doesn’t help to Know Better. It is part of my nature.

Confessing doesn’t help either. I could detail here some of the things that occupy these worthless interludes of longed-for repair, but it wouldn’t do me a bit of good. I’ve learned that sharing embarrassment doesn’t really lessen it, but it does lessen the anxiety you might have that people will judge you for the events in question.

I suggested that a word had been left out of Harlan’s claim. It should have read “I am a petty man too.” He might just as easily have said “I am a compleat human being, having my full measure of all that is human.” That has the advantage and drawback of distracting people from his point, because, while true, it allows for a generous reception and validation of that “compleatness” as an altogether admirable thing.

I think he wanted people to focus on a specific point. “I am a petty man” is the same as saying “It is human to be petty” and therefore, “we’re all petty.”

From time to time, here and there, more or less.

Let me tell you something not petty about Harlan Ellison.

Donna and I attended his last convention, MadCon 2010, in Madison, Wisconsin. We were in the hotel lobby when he came in. It was the first time we had seen each other since 1996. Prior to the convention, when it wasn’t a sure bet that he would make it, due to health issues, I sent him a few photographs I’d taken at that prior occasion. They weren’t great pictures, but I thought he might want them for his archives. In fact, they were pretty much not good. When he realized who I was, he put a hand on my shoulder and said, “Tiedemann, those were the worst pictures in the world. Terrible.” In front of a small audience.

By Sunday, he was dancing on his last nerve, and still signing autographs. I’d given up trying to get one and just lingered at the periphery, and for whatever reason he looked straight at me and said, “Tiedemann, go. Just go.”

I riffled my brain to figure out what I’d done, but he had The Look, and I knew better than to argue, so Donna and I went to dinner.

Afterward, we came back into the hotel. The lobby was empty except for Harlan and Susan. Whereupon he sat down with us and we had half an hour of very good, private conversation. He was generous, interested, and, I think, appreciative, at least of the chance to quietly talk to just one or two people, away from the crowds and the demands of Being On. Whatever, it was special and very, very human. (No, I won’t tell you what we talked about, it’s none of your business.)

As I said, petty gets as petty gives. As far as I’m concerned, Harlan can cop to being petty if he wants, and he would know, but that is simply not my take on him. He gets no petty from me because he’s never given me any.

In the final analysis, we should strive to regard people by their best. If we can’t, at least we should remember that no one is a homogeneity. We are all amalgams. And from certain amalgams, strange alloys, bright, alien, and dark, emerge in gnostic forms and Damascene patterns, texture of nous and passion…

Just a bunch of assorted items of some minor interest.

First up, I did a new interview! Jared Anderson runs a blog specializing in author interviews and he asked me to contribute. Mine is now up, for the pleasure of anyone interested.

Apropos of writerly things, I have finished the second book of my Oxun Trilogy. The first book, Orleans, is currently making the rounds via the good offices of my agent, Jen Udden. Among the various projects I had on hand to work on this past several months, I decided finishing book two might be a good idea. Oculus is finished. At least, it will be once Donna completes picking the nits from it. I hope to hand the manuscript over to Jen some time next week.

This opens the way for volume three, which I intend to call either Orient or Ojo. Haven’t decided yet. Ojo is Japanese for rebirth (roughly) and fits with the theme of the book. This is the one I’m both really looking forward to and dreading, as it will be primarily historical.

Meantime, I am about to dive into the rewrite of my historical mystery, per my other agent’s notes (yeah, two agents, it’s complicated, don’t ask, it works), which will likely take up the rest of the summer.

This afternoon, my friend Russ is coming over with his horn for our last rehearsal before this weekend’s coffeehouse. We’ve been working on a version of Harlem Nocturne, which we both love and hope to do Saturday.

Prior to his visit, I have to go mow the lawn. Tedious but necessary.

In between all that, I’ve been working on some new short stories. As I’ve mentioned from time to time, I’ve been having difficulties with short form for—well, for the last several years. A few months ago I got very angry with myself and just sat in front of the computer, staring at a story fragment, refusing to do anything else until Fred (Fred was the name Damon Knight gave to the unconscious, which he acknowledged but didn’t like calling the Unconscious)—as I say, until Fred belched up the story solution. I promptly finished three or four more and I intend to keep hammering at the others. I must have a couple of dozen half-completed short stories and there is no good reason for them not be completed. Except for Fred.

Donna’s sisters will be coming into town next week (one from Florida, one from Iowa) and, I assume, hijinks shall ensue. In the middle of their visit will be a major party and ongoing we have housecleaning.

I’ve been reading Ray Bradbury, prompted by his death. I wrote about Ray here. The other day I finished Something Wicked This Way Comes and, through the eyes of experience, I marveled at the exuberance of his language, something I sort of took in stride the first time I read it back at age 12 or 14. I’m going to go through I Sing The Body Electric next and then maybe The October Country. Ray was a unique voice in American letters, a high-wire act and a national treasure. Unlike many great artists, he did get acknowledged and rewarded. I think he had an exceptional career, all the more so for having done pretty much what he wanted to do most of the time. He will not vanish into obscurity, I think. He was misidentified as a science fiction writer. What little genuine SF he wrote fell apart on most metrics of good SF, but that’s not what he was trying to do. He was an American mythographer. His stories were about the things that informed our national character, down deep inside where we live, and reflected the romance of a national vision that was fractured at best, overambitious always, and essentially naive. Not that he wrote naively—on the contrary, I think he wrote very perceptively about naivete, and somehow rarely in a judgmental way.

We’re on the threshold of summer. We inherited a gas grill which I need to figure out how to get working, because this year I want to barbecue, something we haven’t done here in years.

There’s more, but I’m rambling. So to conclude, let me offer up another photograph and bid you adieu till next time.

I wish I had recordings. Sometimes, these monthly jam sessions just turn out sweet.

I don’t have much to say about this past Saturday night’s coffeehouse other than everyone had a good time and we had some surprising performances. So rather than try to recapture the musicality, I offer a few images.

Bob is a multitalented player, whose skill I envy. A pleasant surprise was his daughter, Diane, showing up, who turned out (not very surprisingly) to be musically adept as well.

The guy on the right is one of my oldest friends, Tom. Back in The Day we had aspirations to be rock stars. For my money, I got something better—a lifelong friend.

I “premiered” a piece I’d written a long time ago for a friend and colleague, Allen Steele. He wrote a delightful story called Blues For A Red Planet and I couldn’t resist doing something musical with it. Aside from a quote from Holst, there’s not a lot Martian in it, and I’ve never played it publicly before because it requires a decent drummer—which I finally got with Bob, providing the appropriate thunder.

Ended the evening with an unexpected bongo number with our two drummers. Reminded me of some of the percussion moments from Santana concerts.

I don’t post music videos normally, but I thought this was exceptional. It’s music based on China Mieville’s truly excellent novel, Embassytown, which I urge everyone to get, read, immerse yourselves in. This novel goes on my list of “novels to be used to teach science fiction” along with a handful of others. Enjoy.

So what do you do with a bare patch of backyard? Why, put a tree on it!

Donna wanted something for the front yard, which is admittedly rather plain and neglected. We spend most of our time in the back part of the house where the bay windows look out over an increasingly eclectic yard. (Donna keeps saying we need to simplify, get it more low maintenance, but…)

So we bought a Japanese Maple.

We both love Japanese Maples. We bought one shortly after moving into the house and it thrives to this day, but what we wanted was a red one and that first one, after an initial showing of red leaves, turned a lovely green and stayed that way. So we’d always planned on getting another and trying again.

We both love Japanese Maples. We bought one shortly after moving into the house and it thrives to this day, but what we wanted was a red one and that first one, after an initial showing of red leaves, turned a lovely green and stayed that way. So we’d always planned on getting another and trying again.

Donna found it, of course, and after some negotiation, we brought it home. You see it here, newly arrived, next to a piece of scultpure I will now have to move. (We were going to move it anyway, but this has just hastened the day.)

Now, I do not enjoy yard work. It was sort of understood when we bought the house that I wasn’t going to be real big on it, and we agreed to a division of labor. It’s worked out pretty well. I do enjoy the results of good lawn care and the kind of aesthetic experimentation Donna likes to get into. Of course, there’s been overlap, but mostly the yard is her creation.

Usually, the hard part involving me is in deciding where to put what. This time, it was just obvious.

It’s a beautiful tree. We “swiped” some concrete edging from next door (long story, it’s all cool) and after an afternoon’s work we have a new member of the forest in our yard.

Now, of course this wasn’t the end of it. Oh, no. Donna’s last job resulted in considerable neglect of the actual lawn, half of which had become overrun with weeds. So in order to make the new tree more at home, we have proceeded to put down new sod—fescue, to be precise. And that got a little muddier.

Obviously, she’s having a good time.

I think she does great work.

This brief interlude of domestic engineering was brought to you by my fascination with a woman I’ve been in love with for over three decades and who I can’t say enough good things about. I don’t get to brag about her very much…at least, it feels that way to me. So I thought I’d share this.

Now back to our regularly scheduled diatribes. Later.

Last Friday, the 6th of April, I had the pleasure of being on-stage host to Mr. David Gerrold, writer. If you’re not familiar with his work…but what am I saying? Of course you are! Even if you may not know it. David Gerrold wrote one of the most loved episodes of the original Star Trek, the marvelous The Trouble With Tribbles. Even those who don’t especially care for the show tend to like that one.

But if that’s all you’re familiar with by him, then I urge you to correct that lack. David Gerrold is one of the best SF writers in the business. I pointed that out last Friday to a packed house.

Donna and I had dinner with David prior to the evening’s performance. We’d met him long ago so could not say we knew him. Conversation ranged over the map, but kept coming back to writing and voice. I sometimes find it hard not to go on about how much I liked someone’s work, but the fact is he wrote some stories that stuck in my head, chief among them being The Man Who Folded Himself. We talked short fiction, novels, politics, the ill-fated St. Louis Worldcon of 1969 (which he attended and I didn’t) and then did a quick tour with the estimable Jenny Heim of the St. Louis Science Center. The Star Trek exhibit really is very good and it amazed me how much there was, just how long we’ve been living with this fictional universe.

I did a quick minute or two song-and-dance to introduce him, then he took the stage and regaled us with behind-the-scenes stories of working on the original Star Trek and related minutiae (for instance, the episode was initially called A Fuzzy Thing Happened To Me but had to be changed because of a potential conflict with H. Beam Piper’s Little Fuzzy stories).

I still pay too little attention to the credits on television shows, a habit from a childhood like, probably, most others in which the stars of the show were the most important aspects. I did not know till that night that he had written one of my favorite episodes of Babylon 5, one called True Believers, which I thought then and still consider one of the most powerful of a strong series.

Anyway, it was a great evening and I am thrilled to have been invited to be part of it.

Oh, and please note—the photographs were taken by Robert S. Greenfield. You should check out his online galleries.